-

Posts

21589 -

Joined

-

Days Won

82

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Downloads

Everything posted by Yankee4Life

-

Then I can help you. Read this thread right here and will explain why you are having problems.

-

No, what I am trying to say is that if you show me the link I will go to it myself and I'll download it myself. One thing I just remembered. Are you trying to get these mods using a Google Chrome browser?

-

Have mercy Jim! That is a great score!!! 👍

-

10 out of 10, 35 seconds. A good score but just watch how many people fly past it.

-

Please post the links of where you downloaded this from.

-

BallFour you have messed up my schedule! I better explain. I rotate every few days playing the Total Classics mod. I may jump from the 1919 mod to the 1939 mod and over to the 1964 mod. It’s a fun variety and it keeps things interesting for me. That is until your 1998 mod. I am going to be spending more time in here and all those other mods will be ignored and for quite some time. Thanks for a fine mod! Tiger Stadium is in a lot of these mods. I don't know what you mean.

- 3 comments

-

- mvp98

- mvp baseball 98

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

6 out of 10, 77 seconds. The beat goes on.

-

I don't even think the ghosts like it.

-

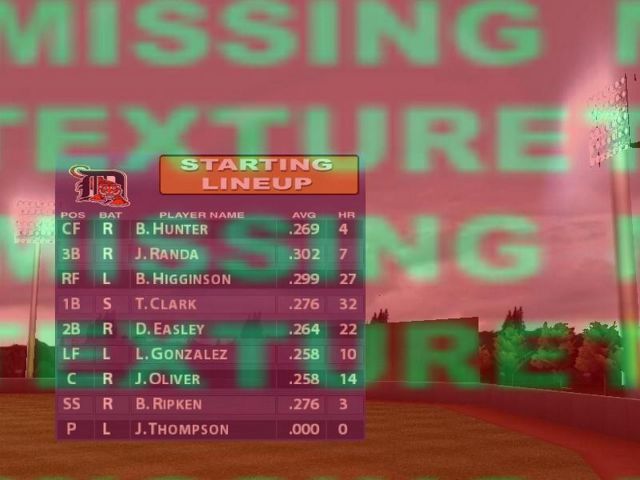

Here are the remaining four ball parks that the missing texture problem was reported. Once I turned off the Cooperstown effect they were all playable. Cashman Field. Jarry Park. Safeco Field (Unfinished). Seibu Dome.

-

1. The designated hitter. 2. Interleague play. 3. Pitchers only being able to throw to first base twice. Can you imagine how many more bases Rickey Henderson would have stolen? 4. Not being able to run into the catcher anymore. 5. That damned Ghost runner. 6. Pitchers must face at least three batters before being taken out. I’m sure there is more. Jim, I have not heard any more about these torpedo bats since the opening week of the season. If these bats were all that that were made out to be then the Rockies would have purchased a dozen of them for everyone on their team. It’s not the name of the bat. It’s who is holding them. And that right there says it all. These idiots can not leave this game alone. EDIT: I have imported KC's list because I agree with every one of them. 1. sponsors on the uniforms 2. new uniforms every year 3. retail on-field uniforms are unaffordable 4. getting into the sport is unaffordable (go ask a dad how much a BBCOR certified bat costs or how much a Rawlings Heart of The Hide glove costs) 5. The Sacramento A's 6. The Rays somehow not working out a long term solution with staying in Tampa or even repairing Tropicana Field 7. Rob Manfred still remaining comissioner 8. The impending lockout

-

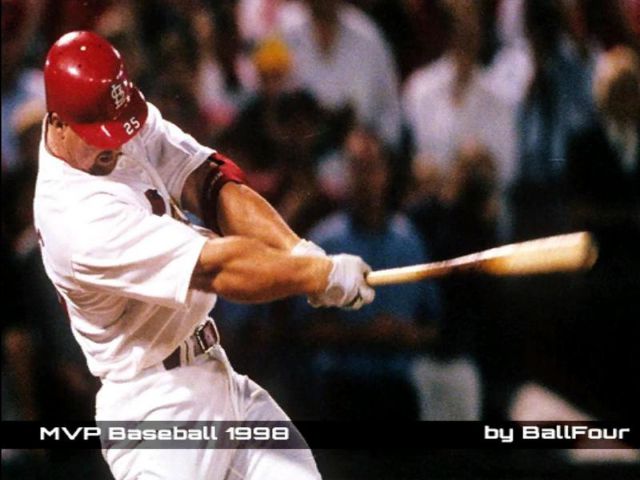

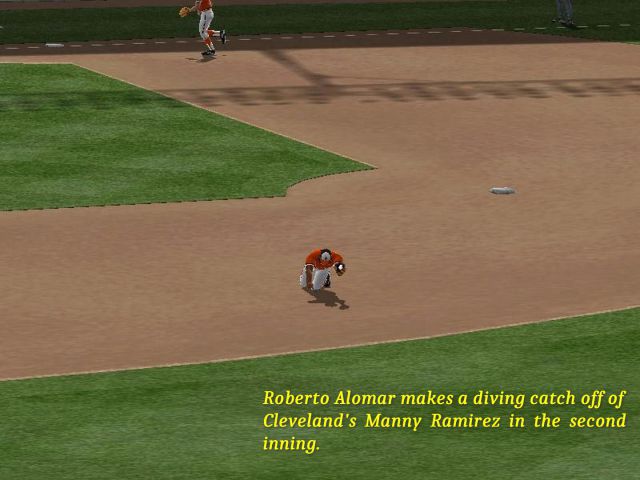

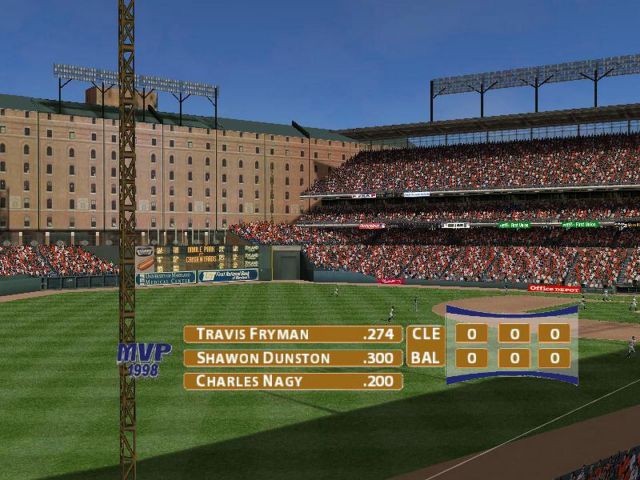

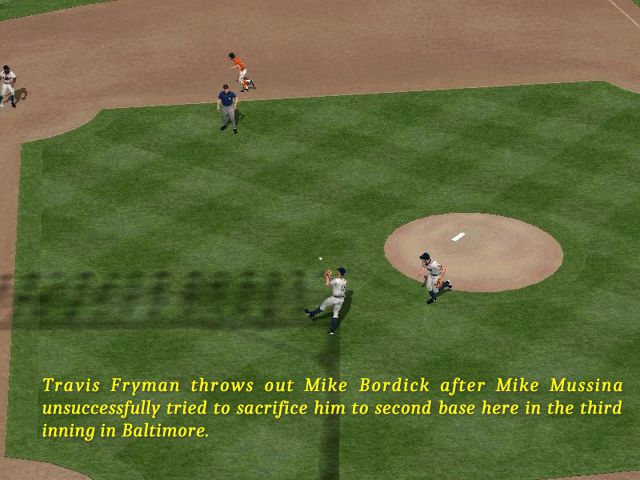

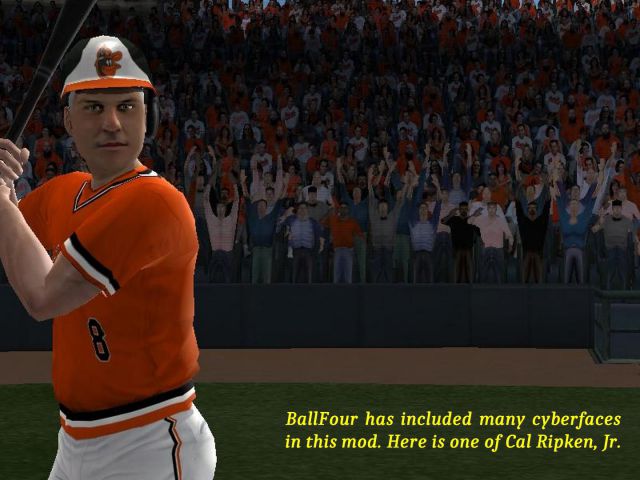

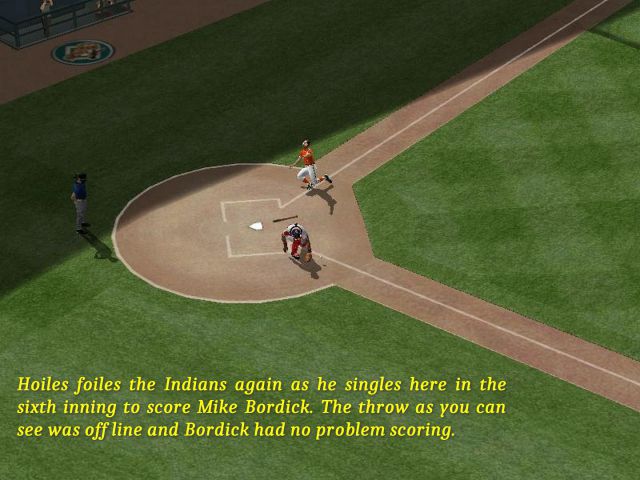

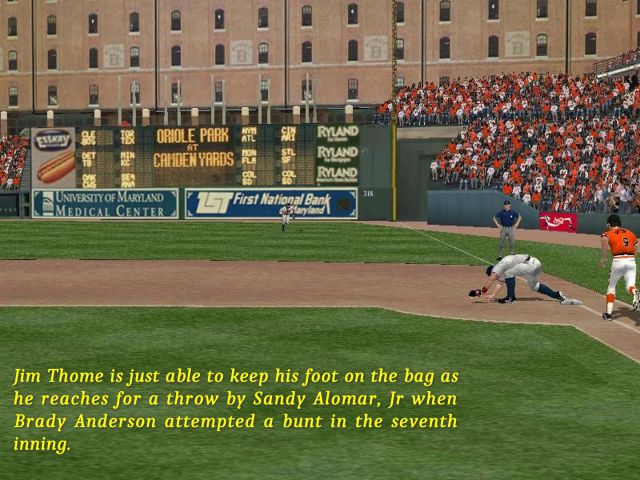

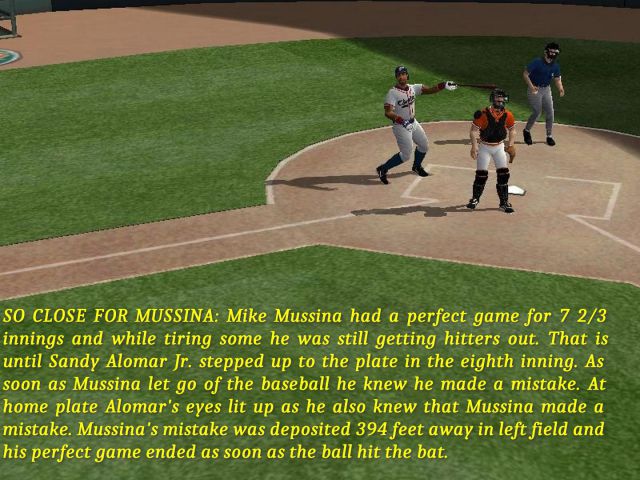

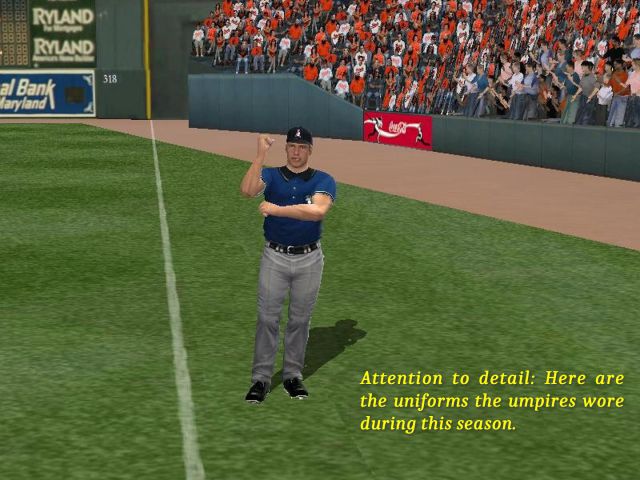

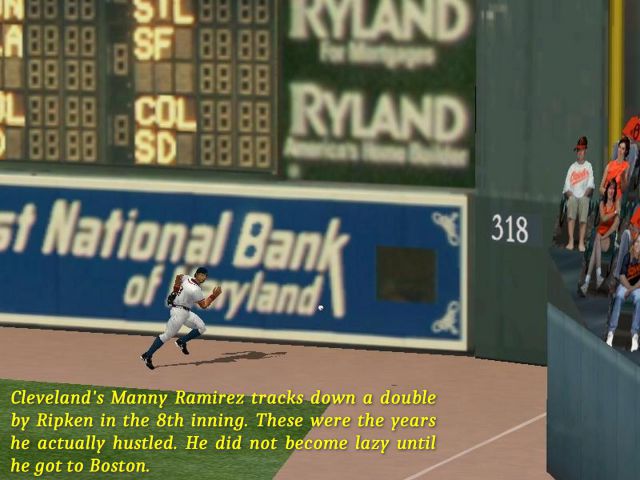

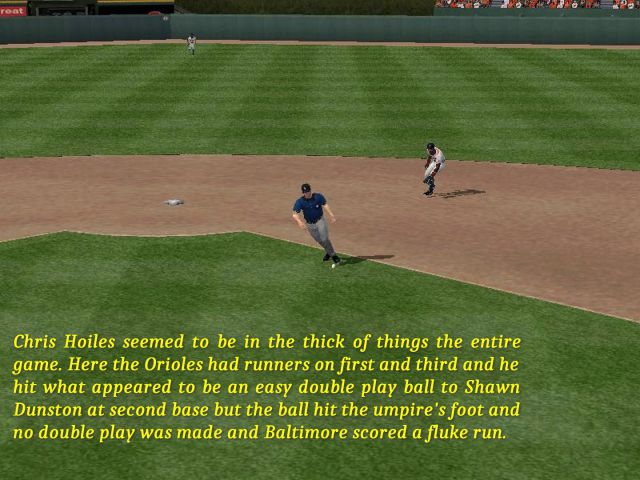

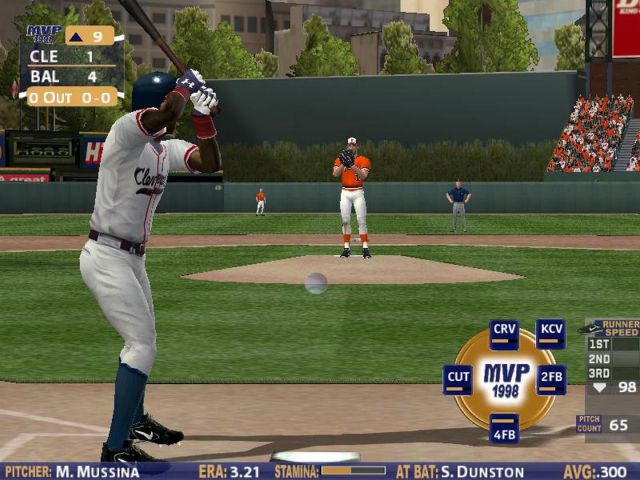

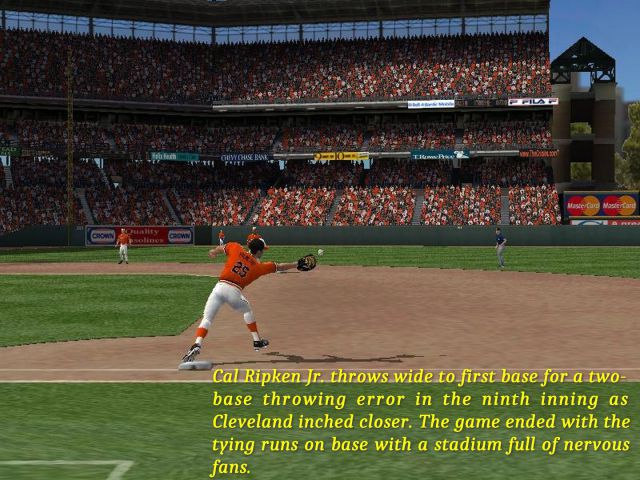

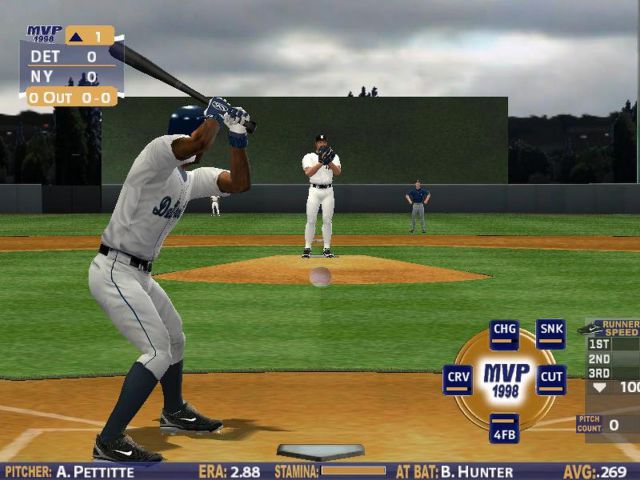

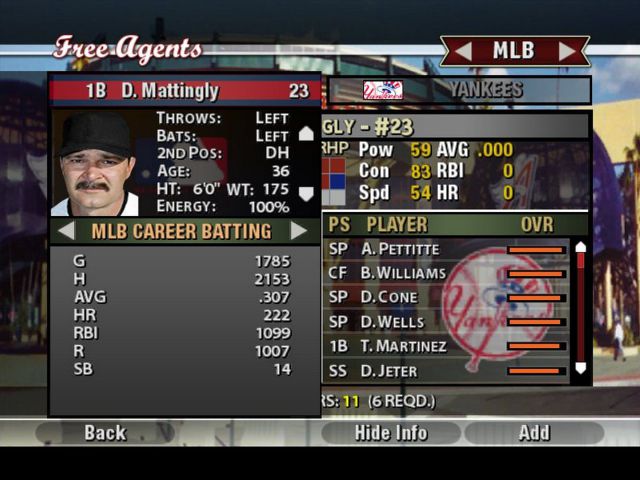

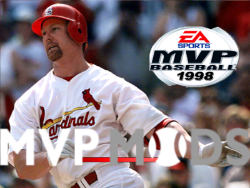

A few years back BallFour announced that he was going to make a Total Classics 1998 mod. Some of you who have been here awhile may recall a modder named Andy82 making the same mod sixteen years ago. The year may be the same but these two mods are in no way identical. It took BallFour many years to finish his mod and despite many frustrations along the way like losing his saved work at the worst possible times and computer issues that caused his system to crash he worked through it and the final result is here for all of us to see. He has turned out a very impressive mod and if you spend just five minutes in it you will see why. BallFour built this mod from scratch in his spare time and before I begin my game review I want to point out that he just did not only assemble the rosters and gather the statistics for each player from the thirty major league teams, he did this for all three levels of the minor leagues (A, AA, AAA) which by itself had to be time consuming. That is one hundred twenty ball clubs with the rosters, home and road uniforms and home ballpark. He has worked on this mod for fifteen years, or five years longer than he’s been a member on this website. Since he has been here he has made an excessive amount of uniforms and if you don’t believe me all you need to do is check out the uniform section in the Mvp ‘05 download area. When he first started making these uniforms and uploading them on what seemed to be a daily basis I said to myself that we had another Dennis James on our hands. That, of course was a compliment of the highest order. BallFour’s uniform work stands alone next to all the great uniform modders that preceded him here. Before I go on any further I should tell you where you can download this mod. Jim825 was kind enough to create an installer for this mod and I have to say again it is the easiest installation of a computer game I have ever seen. Just have a clean install of Mvp baseball 2005 and tell the installer where to insert the files and then just sit back and watch it do the rest. Ok, now that you have got past the click-to-start screen of Mark McGwire swinging his bat the first thing that I notice when I initially go into a new mod is the choice of songs in the jukebox. While he could have easily done so, BallFour did not provide us with the greatest hits of 1998. Instead he inserted the music from nine different baseball video games and if you recognized all nine and played every one of them I salute you. I did not have a Super Nintendo in the 1990’s so I missed the two Griffey games. I found myself listening to the music before picking the teams I used in the game that I covered here and a few others that I have played in over the past few days. The decision to use these audio tracks in this mod was a good one because it brought back some good memories of games I don’t play a lot of anymore. And in case you want a traditional jukebox with songs from that year he has released an alternate menu music mod for those who want that. The free agent pool is the next place I went to because he talked about that in his file description. I never go into the free agent area myself because I have only played exhibition games for the past twenty years. But if you want you can sign players like Don Mattingly (who retired in 1995) or Nolan Ryan (he retired in 1993.) There’s a lot more than these two so if you are someone who wants to play a dynasty in this mod you’ll have some pretty good choices if you decide to sign someone. There is one more thing about the rosters that BallFour told me about. I played a minor league game with the Tampa Yankees, New York’s class A team and the Charlotte Rangers, Texas’ class A team and I noticed something on both teams. Mark Prior was on the Yankee roster and Barry Zito and Carlos Pena were on the Rangers. Zito and Pena were drafted by Texas in 1998 and that is why they were on that team. Another example was seeing Eric Hinske’s name pop up on the Daytona Cubs. As soon as I stop playing a few games I am going to go through every single A roster to see what name pops out for me. These players were put in the low minors and they replaced some single-A players that never made it past the next level. If BallFour had instead placed the players like Zito and Pena in the free agent pool it could have caused a crash in the game. And that was the same answer I received when I asked about Hideki Matsui on Tampa and Ichiro Suzuki for Seattle. As I thought about this I was pretty certain that these single A teams will be a lot of fun to spend time in. Before I go on any further it would not be right of me to omit a very important part of all three minor league divisions. Every minor league team has their regular home and road uniforms on display and the alternate uniforms too. This took a lot of time and research and just by reading his updates in the forum some of these uniforms were not easy to find. And now it’s on to what this and every other total classics mod is about. As I always do I randomly picked two teams for my exhibition game and I settled in on the Cleveland Indians going into Baltimore to take on the Orioles. The Indians were the defending American League Champions and the Orioles won the A.L. East pennant in 1997 so these were two good teams that were about to go at it. Since this was a major league game I played it at Oriole Park in Camden Yards but there are many stadiums included in this mod that catch the eye such as Aloha Stadium in Honolulu (a big ballpark with artificial turf) or the unfinished version of Safeco Field in Seattle or the famous Doubleday Field in Cooperstown, New York. BallFour has a discussion thread where you can provide feedback or report issues with the mod, so if you have any questions about anything just go there to have direct contact with him. Another thing that had to take an excessive amount of time was applying the actual 1997 final statistics of each player who played in the major leagues. I have no idea how many hours it took to finish the complete player history for everyone but it had to be very time consuming. Ok, now I am in the game and for the first time I am going to listen to Krukow and Kuiper. I usually have the sound off when these guys are announcing because they are terrible but I was informed that there is complete team audio for all the teams in this mod and complete audio for every player on each roster that made it up to the major leagues. Now I am not too sure of what really took him the most time, the detailed work of the rosters or the conscientious effort he had to do to get the audio prepared. It was a pitcher’s duel between the Tribe’s Charles Nagy and the Orioles Mike Mussina and it was scoreless for the first four innings of the contest but Baltimore broke through in the fifth via an RBI single by Roberto Alomar and in the sixth an RBI knock by Chris Hoiles made it 2 - 0. While all this was going on Mike Mussina was quietly working on a gem. Seven retired in a row. Then fourteen. And then twenty-one. It was like being at the ball park because as the game went on the stadium organist could be heard in the background thanks to the enhanced organ mod. You may want to have your speakers just a touch louder to really appreciate this.With two out in the top of the eighth he hung one to Sandy Alomar Jr. and Alomar’s eyes lit up. So did Mussina’s but for a different reason. He knew he made a bad pitch but what was even worse Cleveland cut the lead in half. In the last of the eighth good fortune was with the Orioles. With runners on the corners Chris Hoiles hit what looked to be an easy double play ball at Shawn Dunston at second base but there ball hit the foot of the second base umpire and caromed to Dunston’s left. A run scored and everyone was safe as Baltimore scored two runs to take a 4 - 1 lead. A tiring Mussina went out for the ninth and gave up two more hits and Cleveland scored an unearned run when Cal Ripken, Jr. threw the ball away. With two out and the tying runs on base Mussina got David Justice to pop out to end the game which put an end to one of the best games I’ve played in quite some time. I would have liked to have shown a perfect game to everyone but I came close. The Indians of that era were a very good team. I want to thank BallFour for making this mod and I recommend this to everyone who is a fan of Total Classics and Mvp Baseball. Welcome to Total Classics 1998! A packed house in Baltimore between these two good teams. The overlay used in this mod. Final score: Baltimore 4, Cleveland 2. Thank you BallFour for this mod!

-

5 out of 10, 100 seconds. Just once I'd like to start a month off good. And thanks for the information on the Liverpool soccer stadium yesterday Jim. I had no idea.

-

This is perfect BallFour! Check it out everyone. Cooperstown effect ON. Cooperstown effect OFF Doubleday field, same two teams.

-

4 out of 10. This is getting ridiculous. I can't stand Tuesdays. Look at the questions I got. The final event in the decathalon was the 1500m. Who won this event in Athens to take the last place in the decathlon all-star team? Who won the Norm Smith Medal? Who the hell is Norm Smith? England only used 12 players throughout the series. Who replaced Simon Jones in the final Test at the Oval? What was the home ground of Liverpool? What was the home ground of Sunderland? No wonder I missed all of these!!

-

looking to accquire mvp baseball 2005 pc cd

Yankee4Life replied to ikz's topic in Left Field (Off-Topic)

That is exactly it. -

Sabugo, I'm sorry that your father has been gone so long but trust me you will never have a hard time remembering both your mother and father. Our memories are our own private scrapbooks. Your father sounded like a very interesting guy and I would have loved for the opportunity to shake his hand. He would no doubt be proud of the way his son turned out. I think it is a great idea to write down memories of him and maybe keep adding to it when you think of something else. Your son will love it.

-

8 out of 10, 86 seconds. Slow time today but a lot of these questions I had to think about.

-

i don't believe this! I did 34 seconds and I thought I had a good day. It shows how much I know. 😄

-

10 out of 10, 34 seconds. Now that is the way to start a month. Here are the final standings for May. Congratulations Jim! 👍

-

What was your name when you were here before?

-

All you have to do is go to the downloads and see for yourself what is there. There is NO 1935 or 1936 mod and you would have seen this for yourself had you looked!!!!!!

-

10 out of 10, 67 seconds. At least I ended strong. 🤷♂️

-

-

Not bad? You did great!

-

10 out of 10, 36 seconds. What a month! 😄

.thumb.jpg.a077d0cb812a43ba39aa2c5e3a6c935c.jpg)