-

Posts

21533 -

Joined

-

Days Won

82

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Downloads

Everything posted by Yankee4Life

-

Ok, let's try this. Download this overlay right here and follow the directions. Unzip the igonly.big and ingame.big files to your MVP Baseball 2005\data\frontend directory. Please as always, back up the original files first. Enjoy! Since you are having this problem with your current overlay I want you to do this. Go in that directory and delete the current igonly.big and ingame.big files that are currently in that directory. After you are done doing that unzip this overlay and be SURE to place these two files in the MVP Baseball 2005\data\frontend directory. Now you should be ok. If you want to install other overlays please back up these two files. It is a very simple process.

-

Thank you Jim! 🙂

-

That I don't know. I use a Logitech gamepad that has not failed me once. Why you need a PS3 or 4 controller is beyond me.

-

Yes it is still the case that this game and Windows 11 do not get along. Keep in mind that this is a twenty-year-old game.

-

Great and Historical Games of the Past

Yankee4Life replied to Yankee4Life's topic in Baseball History

This is a game that I have always wanted to see. What a comeback by the Yankees in this one and I would have loved to see Ebbets Field also. World Series Game Four--New York Yankees vs. Brooklyn Dodgers (October 5, 1941) A blue envelope arrived at Ebbets Field via telegraph on Monday, October 6, 1941. Brooklyn Dodgers catcher Mickey Owen’s name was on it, along with the words “Personal Delivery Only.” The sender was a 10-year-old boy, a Dodger fan who scrounged up some coins and begged his mother to help him mail a letter to his favorite player. “My son has worshipped Mickey Owen all year and said he felt Mickey might go to pieces after that mistake he made yesterday if he didn’t get enough encouragement to carry on,” the boy’s mother said. Owen reportedly kept the note in his uniform pocket for Game 5 of the World Series. It wasn’t the catcher’s fault the Yankees beat the Dodgers in the 1941 World Series, but history has already rendered its narrative. Owen’s dropped third strike with two outs in the ninth inning of Game 4 was so dramatic, so ill-timed, and so integral in turning a 2-2 series tie into a 3-1 Yankee lead, no one needs years of perspective to identify a scapegoat. A 10-year-old could figure out who needed a pat on the back before the next game even started. This narrative misses a crucial fact, however. The first eight innings of Game 4 represented the Dodgers at their most dominant in decades. From Kirby Higbe’s first pitch until Hugh Casey threw what might have been the last, the mighty Yankees--winners in four of the previous five World Series--appeared to have met their match in Brooklyn. While the European theater of World War II raged like an inferno, Brooklyn was experiencing its own heat wave. Ebbets Field reached 96 degrees during the afternoon of Game 4, a record for the city on that date but not enough to deter 33,813 fans. It was only a few degrees cooler the day before, when the Bronx Bombers took a two-games-to-one lead in the series. After seven scoreless innings, the Yankees scored twice off Casey to win 2-1. It was the third consecutive one-run game to begin the series. The first postseason game at Ebbets Field in 21 years ended in Dodger defeat. Atley Donald was scheduled to take the ball for the Yankees in Game 4. Brooklyn starter Kirby Higbe spotted him a one-run lead. The Yankees sent six batters to the plate in the top of the first inning, and got their run when Charlie Keller singled in Red Rolfe. In the fourth inning, still leading 1-0, the Yankees loaded the bases with no outs. Keller was forced out at home plate, but Johnny Sturm’s two-out single put the Yankees ahead 3-0. That was the last pitch Higbe would throw, as Larry French was summoned from the bullpen to record the final out of the inning. Donald blanked the Dodgers for three innings. In the bottom of the fourth, Owen and Pete Coscarart drew walks with two outs. Pinch-hitter Jimmy Wasdell drove in both runners with a double, drawing the Dodgers within 3-2. In the fifth, the Yankees loaded the bases again with two outs, and Casey was summoned from the bullpen for the second straight day. Dodgers general manager Larry MacPhail had publicly criticized his 27-year-old pitcher--and even the Dodgers’ bullpen catcher--for not warming up faster in Game 3. Casey must have learned his lesson; he looked plenty warm when Joe Gordon hit a fly ball for the third out. The Yankees didn’t get a runner past first base against Casey until the fateful ninth inning. If not for Owen’s dropped third strike, Pete Reiser would have been remembered as the game’s hero. He certainly earned it. The 1941 season was a career year for several Dodger players and none more than Pistol Pete, who led the National League with a .343 batting average. In his first year as the Dodgers’ everyday center fielder, Reiser finished second to Camilli in voting for the Most Valuable Player award. With Dixie Walker on second base and none out, Reiser hit a two-run home run to right field over the Ebbets Field scoreboard6 to give the Dodgers a 4-3 lead. The way Casey was pitching, the score wasn’t likely to change. Casey was “making a hollow mockery of the vaunted Yankee power,” wrote the Philadelphia Record. “The Yanks had gone into that ninth (inning) a beaten team,” wrote the Boston Post. Sturm and Rolfe grounded out to begin the final inning. Two down, one to go. Casey went to a full count against Henrich and Owen called for a curveball. This proposition wasn’t as simple as it seems. “Casey had two pitches--a fastball and a curve,” Owen told Sports Illustrated in 1991. He continued: But he had two of each. He had a fastball that would either rise or sink. And he threw a big overhand sharp-breaking curve or a hard, quick curve that was a little bit like a slider. When he came into the game in the sixth inning, we both realized that the big curve wasn't working. So whenever I gave him the signal for a curve, he threw the quick one. Then, with the count 3 and 2 on Henrich, I signaled for the curve and Hugh rolled off a big-breaking curve that was probably the best he ever threw in his life. It broke down and in to Henrich, a left-handed batter, just as he swung at it. Years later, Henrich called it “one of the best and craziest curveballs I’ve ever seen.” Owen, however, told Sports Illustrated that he wasn’t expecting that curveball. “I'm expecting the quick curve and couldn't get my glove around to handle the ball when it broke so sharp,” he said. “Then the ball hits the heel of my glove and rolls back toward the stands as the cops were coming out to keep fans off the field.” The public address announcer, Charlie Clark, said the ball nearly reached his seat in front of the backstop: “Mickey came after it with a big vacant stare on his face--disbelief. I got out of his way because he could have bumped right into me, but I felt like kicking it back to him so he could get Henrich going down to first. I could have been famous.” What happened next sealed Owen’s notoriety, but the Yankees deserve credit for rallying. DiMaggio singled. Keller doubled, scoring Henrich and DiMaggio and giving New York a 5-4 lead. Dickey walked. Then Gordon doubled, scoring Keller and Dickey to make it 7-4. Johnny Murphy pitched a scoreless ninth inning. They were the heroes; immediately afterward Owen conceded, “I guess you’ll have to call me the goat of the game.” One out away from a 2-2 tie, the Yankees forged a 3-1 lead in the best-of-seven series. Rather than reviling the catcher, Brooklyn embraced Owen. “I got about 4,000 wires and letters,” he told the Saturday Evening Post. “I had offers of jobs and proposals of marriage. Some girls sent their pictures in bathing suits, and my wife tore them up.” Brooklyn lost Game 5 the next day at Ebbets Field, 3-1, ending the series. With the young fan’s note in his pocket, Owen received a “tremendous ovation” in his first at-bat. The pats on the back kept coming, and the role of 1941 World Series scapegoat followed Owen to the end of his life. Embraced by his city, Owen was able to embrace his role in history. “I would’ve been completely forgotten,” he said years later, “if I hadn’t missed that pitch. Tommy Henrich The Dodgers have just won game four of the 1941 World Series as Tommy Henrich strikes out for the final out of the game. Or has he? As you see here Henrich swung and missed, which would have ended the game, but Dodger catcher Mickey Owen failed to catch the ball and Henrich reached first base. Joe DiMaggio followed with a single and Charlie Keller hit a double to drive in Henrich and DiMaggio and take the lead. Bill Dickey would follow up with a walk and, along with Keller, score on a Joe Gordon double to make the final score 7–4. -

10 out of 10, 31 seconds. This is the best score I've had in months.

-

Mule Haas The October 3, 1929, issue of the Sporting News printed a sampling of observations of beat writers from around the Major Leagues with their predictions on who would win the World Series between the Philadelphia Athletics and the Chicago Cubs. Of the 106 writers polled, 53 picked Philadelphia, 42 liked the Cubs, and 11 others abstained from making a choice. Although both squads could rip the cover off the ball, the scribes pointed to the strength of the A’s battery. Philadelphia boasted one of the best backstops ever in Mickey Cochrane, while the Cubs had Zack Taylor and Mike Gonzalez, who were filling in for the injured Gabby Hartnett. Pat Moran, who led the National League in wins with 22, led a fine Chicago staff that included Guy Bush and Charlie Root. George Earnshaw, a strapping right-hander, led the junior circuit in victories with 24. He was joined by 20-game winner and ERA champ Lefty Grove, 2.81 and Rube Walberg. The cunning Mack stacked the deck against the Cubs’ dominant right-handed bats. He inserted the right-handed Howard Ehmke in the rotation while Grove and Walberg, both lefties, pitched out of the pen. Those writers who selected the Athletics may have been on to something. Philadelphia won the first two games of the Series, as their pitchers combined for 26 strikeouts. The Sporting News lent some humor, accurate as it was, in their October 17 edition with the headline, “They Were From The Windy City, So They Fanned Up Quite A Breeze”. The Cubs came back to win Game Three, and looked well on their way to evening up the Series as they raced out to an 8-0 lead in Game Four. Root was pitching a three-hitter when the A’s erupted for 10 runs in the seventh inning, won the game, 10-8, and took a commanding lead in the series. The Cubs led, 8-6, in that eventful seventh when A’s center fielder Mule Haas greeted relief pitcher Art Nehf with a shot to center field that Hack Wilson lost in the bright sun. The result was an inside-the-park home run that narrowed the Cubs advantage to a single run, 8-7. Earlier in the inning, Wilson had lost sight of the ball on a single by Bing Miller, also because of the sun. “I don’t blame Wilson a bit,” said Haas. “Believe me that sun was terrible out there and maybe I got a break that I didn’t lose one myself.” Chicago manager Joe McCarthy said, “You can’t beat the sun, can you?” Ed Pollock of the Philadelphia Public Ledger wrote that after Haas’s home run; “The A’s dugout was seething with joyous and romping players. The retiring McGillicuddy found himself being jazzed around and embraced by a demonstrative employee. A dozen pair of hands reached into the bat pile, so neatly arranged in front of the dugout and sent the lumber skyrocketing in disorder.” Game Five followed the same script, as Malone was throwing a two-hitter at the A’s and nursing a 2-0 lead. Philadelphia manager Connie Mack sent pinch-hitter Walter French to the plate to lead off the bottom of the ninth inning. Malone struck him out, but the fans at Shibe Park came alive when Max Bishop singled down the third base line, and Haas again came through. This time his homer left the park, over the right field fence and just like that, the A’s had knotted the score. Miller later doubled home Al Simmons with the winning run to give the Athletics the World Championship. “I could see myself going back to Chicago before that ninth inning,” said Mack, “and I was wondering whom I would pitch in the next game there. I had my reservations made and my tickets bought.” Chicago shortstop Woody English was having the same thought as Mack. “All we needed was three more outs and we were back in Chicago for the last two games. It looked like we had it salted away.” Haas recalled the at-bat. “That hit of Bishop’s in the ninth inning inspired me when I went up to the plate in [the] ninth,” said Mule. ”It was a ‘do-or-die’ inning for the Athletics. I knew that Malone would try to breeze over the first strike. That’s what he gave me, a fast ball and high. It was money from home for your little Georgie. I swung hard, and when I saw that ball going over the right field stand, well, I can tell you just how I did feel. It was a grand and glorious feeling. Then too, I got a great kick out of the crowd yelling in the stands. I’m the happiest kid in the world to-night.” George William Haas was born on October 15, 1903, in Montclair, New Jersey. He was the second child (brother Howard) of George and Marguerite Haas. The elder George tried his hand at baseball, pitching for a couple of semi-pro teams. He made his living working as a plumber for the water department. Often young George would serve as his dad’s apprentice in his formative years. Hass attended Montclair High School. His intent after high school was to attend Columbia University and take business courses. However, one day his shoes were taken from the high school gymnasium dressing room. He could not afford another pair and demanded that the school purchase him a new pair. The principal declined to accommodate Haas, and he abruptly left school. Haas decided to focus his efforts on semi-pro baseball and working with his father, knowing full well that he would lack the necessary credits to attend Columbia. “I was chasing the outfield for a team in Orange, N.J.,” recounted Haas. “Towards the end of the summer, a couple of big-league scouts made me offers. One of the scouts was Jim Johnstone, a former National League umpire who worked a lot of our games, and the other was Mike Drennan of the A’s. “Well, I listened to both their offers and made a date to see them again the next day and give my answer. The way it turned out was Johnstone saw me first and I signed with him, for Pittsburgh, without waiting a half hour more to keep my appointment with Drennan. Believe me, not waiting those 30 minutes cost me plenty of punishment in the next few years.” The Pirates assigned Haas to Williamsport of the New York-Pennsylvania League in 1923. Haas scuttled through the Pirates’ farm system the next few years. The left-handed swinging Haas showed a propensity for hitting the rawhide. He could also run like a deer and covered a lot of ground from his center field position. Haas also exchanged “I do’s” with the former Marie Stucky of Caldwell, New Jersey. They had one child, a son, George Jr. In 1925, Haas found himself in another league, as he was assigned to Birmingham of the Southern Association. He hit .316 for the Barons, and shared the team lead in doubles (27) with Stuffy Stewart. It was in Birmingham that his moniker “Mule,” was given to him. Although the tale varies a bit, Haas summed up the story. “I hit the ball all over the ballpark one day, and this sportswriter [Zip Newman] said ‘my bat packed the kick of a mule,’ The nickname caught on and that was it.” Haas was recalled by the Pirates and made his major league debut on August 15, 1925, pinch-hitting for Max Carey in the sixth inning. He got aboard on a force play and came around to score for the Pirates’ only run in an 8-1 loss to Cincinnati. Pittsburgh won the World Series in 1925, besting the Senators in seven games. They were loaded with talent in the outfield, with Kiki Cuyler, Clyde Barnhart and Carey. For that reason, Haas was sold to Atlanta, and found himself back in the Southern Association. Over the next two seasons, Haas roamed the outfield and continued to hit the league’s pitching. In 1927, Haas hit .323 and led the Crackers in doubles (34) and home runs (10), and tied for the team lead in triples (19). Drennan had been following Haas’s career even after he got the stiff arm from the youngster a few years before. Connie Mack was looking for an infusion of youth into his outfield. Drennan gave Mack two choices; Haas of Atlanta and Eddie Morgan of New Orleans. One of Mack’s former players, Frank Welch, was a teammate of Haas’s and played against Morgan. When Mack asked Welch for his opinion, Frank replied, “Right now, I prefer Haas to Morgan. Morgan is a very young player and you can’t tell how far he can go, but today Haas has it on him in every particular.”Based on the advice of Drennan and Welch, Mack purchased Haas for $10,000. When Haas joined the club for the 1928 season, a – future member of the Hall of Fame offered him sound advice. “Before I came to the A’s, I always held my bat at the very end of the handle,” said Haas. “But Eddie Collins took me aside one day and showed me a new way to grip the bat. He shortened my grip and I began hitting pitches I used to only nick. I’ve been batting with a shortened grip ever since.” He bided his time on the bench, as he did not show much hitting early in the season with his new grip. On July 25, Ty Cobb was struck in the chest with a pitch, and Haas replaced him in the starting lineup. On August 22, the Athletics and Indians were tied up in a marathon game at Shibe Park. Johnny Miljus, a pitcher who employed the slow-pitch to keep batters off balance, had made Haas look foolish on a previous at-bat. But Haas stepped to the plate in the bottom of the 17th inning, and connected for a home run, giving the Athletics a 6-5 win. Mack was putting together a competitive club. The outfield was as good as any in the majors with Al Simmons, Haas and Miller. Jimmie Foxx played first base, Max Bishop was at the keystone position and Jimmy Dykes manned the hot corner. Cochrane had few peers at catcher. In 1928 they finished 2 ½ games behind the Yankees. Although they compiled a 98-55 record, their head-to-head record of 6-16 against the Bronx Bombers was reason enough for the A’s to land in second place. But they would not be bridesmaids for the next three seasons, as Mack’s juggernaut won the American League flag three years in a row from 1929 through 1931. Haas had career highs in home runs (16), RBIs (82), hits (181), runs (115), doubles (41) and triples (9) in 1929. He would not come close to duplicating that output for the rest of his career. But there were two other areas where Haas had excelled. One of those was the art of the sacrifice, as he led the A.L. in six of seven years (1930 -1936) in sacrifice hits. The other bit of expertise that he gave the Athletics was that of a bench jockey. “Well you can’t holler if you don’t have a good voice,” explained Haas. “You have to holler to be heard. First, you must have the vocal equipment. Second, a little finesse. You can’t get away with that rough stuff that used to be the real thing years ago. Third, you have to be a sort of student of all the players, and you must pick out little quirks. And you’ve got to be in on the gossip around the league. Little incidents can be built into juicy items for the jockey.” The Philadelphia Athletics met the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1930 World Series. They toppled Gabby Street’s bunch in six games behind Grove and Earnshaw, who each won two games. As good a hitter as Mule was in the regular season, he could not find the stroke in the post-season. Even though he got the big hits the year before against the Cubs, he batted a pedestrian-like .238. Against the Redbirds, his average sank to .111. Haas hit a career-high .323 in 1931. He had two five-hit games. The first one was a Philadelphia-Cleveland slugfest won by the A’s, 15-10, on May 17. The second came almost a month later on June 19. This time they clobbered the Chisox, 10-4, at Comiskey Park. The Athletics went 69-20 through May, June and July, and coasted to their third pennant in 1931. The series was a rematch with the Cardinals, and this time around St. Louis bested the A’s in seven games. Haas again sputtered on offense, batting a woeful .130. The following season New York regained first place, outdistancing Philadelphia by 13 games in 1932. In the midst of the Great Depression, attendance had declined. The A’s drew 405,500 in 1932. It was their lowest figure in eleven years. Mack viewed Foxx, Cochrane and Grove as his untouchable players, while the rest of the team carried a price tag. Mack had a premise about trading or selling ballplayers to other clubs. “None of the five ranking clubs in the league will ever be able to buy or trade with me for a player as long as I am a manager. They are always well-supplied with players and that is as strong as I want to see them.” After some haggling with the White Sox, Mack sent Simmons, Dykes and Mule to the Windy City for $150,000. Simmons and Haas said all the right things, acknowledging their respect for Mack and the realization that there was nothing personal. It was about Mack recouping money for his franchise. Mack was right on target when describing his trading partners, as the White Sox were a second-division team in the A.L. While all three players played well, it was the lack of first-line pitching that was their downfall. Dykes became a player-manager in 1933, and acquired Earnshaw from the Athletics to try and bolster the staff, to no avail. “Haas is a retiring sort of player,” said Simmons. “He never has much to say, but he’s trying all the time. If he’s in a slump, he doesn’t worry. If he’s going good, he doesn’t get overconfident. I’d set him down as a good, steady ballplayer. Perhaps he’s slowed down a bit, but he can still move around with the best of ‘em in the outfield.” Simmons’s assessment of his fellow outfielder was right on target. From 1933 through 1936, Hass was a regular in the Sox lineup, first in center field, and then in right. He batted a solid .283 during these years. But the Sox acquired Dixie Walker on waivers from the Yankees in 1936. Walker was inserted in right field in 1937, pushing Haas to the infield as a backup first baseman. Mule was released after the 1937 season. He returned to the A’s in a substitute role in 1938,then retired with a .292 career batting average, 254 doubles, 45 triples, 43 home runs and 496 RBIs. As a center-fielder, Haas had a career fielding percentage of .984. After his major league career, Haas managed Oklahoma City of the Texas League. He returned to Chicago to join Dykes’s staff as a coach from 1940 to 1946. He returned to the minor leagues, managing Hollywood of the Pacific Coast League (1947), Montgomery of the Southeastern League (1948), and Fayetteville of the Carolina League (1949). Haas returned to Montclair as athletic director at Fort Montclair, coaching the basketball and baseball teams. One of his players was future Yankee great Whitey Ford. Later in life, he worked as a pari-mutuel clerk at Monmouth Park. One of his co-workers at the racetrack was former pitcher Bullet Joe Bush. In 1974, Haas was driving down to New Orleans to visit his son, George. He suffered a minor stroke en route, but continued his trip. While visiting, he suffered a bigger stroke and collapsed. He passed away on June 30, 1974. Mule Haas was well-known as a creative and loud bench jockey. But he wasn’t always that way. “I wasn’t always gabby on the bench,” said Haas. “When I had those trials with the Pirates, I used to keep my mouth shut. In fact, one day years later when I bumped into Bill McKechnie [his old Pirates manager], he said to me, ‘Do you talk yet?’” One of his favorite foils was Boston slugger Ted Williams. “Ted didn’t have much of a sense of humor when it came to a riding from the opposing bench,” said Mule. “We really got on him after he gave an interview saying he once considered being a fireman. Well, every time he came up, we’d sound off like sirens and bang on any pipes in the dugout. That used to get him.”

-

Great and Historical Games of the Past

Yankee4Life replied to Yankee4Life's topic in Baseball History

What an unbelievable game this was. No game is ever out of reach in Fenway Park and this one proved it. Swisher, Teixeira help Yankees rally from 9 runs down to blow out Red Sox BOSTON — Acts like this figured to be tougher for these 2012 Yankees. These Yankees traded their offensive player with the most upside, Jesus Montero, in order to upgrade their starting pitching. And that upgrade, Michael Pineda, experienced a setback in his right shoulder yesterday, and now nobody knows when, or if, Pineda will make his Yankees debut. But the Yankees pulled off their most important, most improbable victory of this young season yesterday, coming back from a nine-run hole to post a 15-9 win over Bobby Valentine’s hapless Red Sox at Fenway Park, because of an early improvement from an unlikely source. Nick Swisher? The guy who seemed to come up so small so often in pressure situations is now thriving in his walk year? The guy who, if the Yankees are serious about cutting payroll, won’t be back next year? “Last year was a super stressful season for me, man,” Swisher said, after he set a new career high with six RBIs. “I am not going to be stressed out like that this year. I’m going to have as much fun as I can and just enjoy it. This is such a great place to play. I’m just enjoying every minute of it.” When Boston’s starting pitcher Felix Doubront put up a zero in the top of the fifth, making the game official, the Yankees trailed by a 7-0 margin, with the Red Sox having knocked out Yankees starting pitcher Freddy Garcia in the second inning. Rookie David Phelps, finally appearing human, allowed two more in the bottom of the fifth. This one looked over, with Boston cruising to a much-needed win. Yet as manager Joe Girardi said later, echoing his mentor Don Zimmer: “In this park, a lot of things can happen.” It was Swisher whose seventh-inning grand slam changed the game, pulling the Yankees within 7-5. His fellow switch-hitter Mark Teixeira added a three-run blast, scaring the daylights out of the Red Sox before they escaped the inning up, 9-8. The Red Sox are a train wreck most of all because of their bullpen, so give Valentine credit for going to his closer, former Yankee Alfredo Aceves, to try to get a six-out save when Franklin Morales gave up a leadoff single to Eduardo Nunez in the eighth. To whom else could Valentine turn? Aceves, however, pitched horribly. He walked Derek Jeter, the other guy in this lineup who has provided an early improvement. And then Swisher slammed a double off the center field wall, driving home Nunez and Jeter to give the Yankees a 10-9 lead. Swisher, standing on second base, emitted a joyful holler. “If you come back from nine runs against anybody, it’s a cool thing,” said Teixeira, who homered once from each side of the plate. “But here in Boston, it makes it a little more fun.” “Against the Red Sox, to be able to come back and pull that win off, that’s a big win for us, man,” said Swisher, whose 20 RBIs lead the American League. “That’s a huge momentum shift for us. This team, we never give up.” Swisher started last season horribly, compiling a lowly .639 OPS with just three homers through May 29, before waking up some — and then contributing a characteristically poor postseason. He admits now that he let his contract situation get to him. The Yankees held a $10.25 million option on him for 2012 that they exercised. “That option, I’ve never been through something like that,” Swisher said. “This year, I’ve done all my work in the offseason. I’ve done all the things that I wasn’t ready to do, worked with my sports psychologist, stuff like that. I’m just in a good place. Really just enjoying everything. Whether I go 4-for-4 or 0-for-4, my mental preparation stays the same every day.” The Yankees want to lower their payroll to $189 million by 2014, to save money on the luxury tax, and the only way they can do that while retaining Swisher is by letting either Robinson Cano or Curtis Granderson go. That’s unlikely. So the Yankees will enjoy this unexpected upgrade while it lasts — and that goes double for this Red Sox swan dive. April 21, 2012: Yankees rally from 9 runs down to blow out Red Sox While fans lament the Red Sox collapse of 1978, their 2011 collapse was actually worse. The Sox entered September with a nine-game lead only to lose not only the division, but a wild-card berth as well in what was an epic final day of the 2011 season. There were reports that the Red Sox pitchers had been drinking beer and eating fried chicken in the clubhouse and dugout during games. It had appeared that skipper Terry Francona, who led the Red Sox to two World Series titles and helped break the “Curse of the Bambino,” had lost control of his players. The chicken and beer scandal led to the end of Francona’s tenure in Boston. The front office decided that the new Red Sox manager would need to restore order in the clubhouse, and that Bobby Valentine was the man to do just that. The Red Sox began the 2012 season on the road, where they lost five of their first six games. It seemed that the friendly confines of Fenway Park could be the remedy as they won the first three of four games in their home opening series against the Tampa Bay Rays. After dropping the last game against the Rays, the Red Sox were then swept by the Texas Rangers and their hated rival Yankees came to town for a two-game series. The first game was the 100th anniversary of the opening of Fenway Park and resulted in another Red Sox loss. Red Sox fans could only hope for a different result in the second game. After the the Yankees went down in the top of the first, the Red Sox’ bats heated up quickly against Freddy Garcia, starting with Ryan Sweeney reaching out across the plate to bloop a one-out double down the left-field line. After Garcia got Dustin Pedroia to hit a pop foul for the second out, Adrian Gonzalez just missed a home run; the ball bounced over the short fence in right field, scoring Sweeney and putting the Red Sox on the board. David Ortiz’s double to left scored Gonzalez, giving the Red Sox a 2-0 lead. The Red Sox continued to hammer Garcia in the second, starting with a one-out single by Cody Ross, who took third on a double by Darnell McDonald off the left-field wall. Mike Aviles’s single scored Ross and sent McDonald to third. He scored on Sweeney’s sacrifice fly to right. After swiping second base, Aviles scored on an opposite-field single by Pedroia that ended Garcia’s afternoon. Gonzalez’s flyout to deep center field off reliever Clay Rapada ended the Boston threat with the home team leading 5-0. Boston tacked on two more in the third. Ortiz led off with a single to right field. David Phelps replaced Rapada and hit Kevin Youkilis in the hip with his second pitch. Jarrod Saltalamacchia’s single to right loaded the bases with no outs. McDonald’s sacrifice fly scored Ortiz and Aviles’s single plated Youkilis, extending the Red Sox lead to 7-0. Saltalamacchia led off the bottom of the fifth with a 420-foot double to the deepest part of Fenway Park in center field. Ross’s blast to center cleared the fence and made it 9-0, Red Sox. Red Sox starter Felix Doubront kept the Yankees off the scoreboard for the first five innings and struck out Robinson Cano and Alex Rodriguez to start the sixth. Switch-hitting Mark Teixeira, looking for a fastball from Doubront, deposited a 2-and-1 offering into the seats above the left-field wall, putting the Yankees on the board, 9-1. Valentine replaced an effective Doubront with reliever Vicente Padilla to start the top of the seventh. Andruw Jones struck out looking to lead off the seventh. Russell Martin hit an opposite-field bloop single to right. Eduardo Nuñez reached safely on a weak grounder to third. After Derek Jeter walked, Nick Swisher stepped to the plate with the bases loaded and none out. Swisher entered the 2012 season trying to shake off another poor postseason performance, and was off to a great 2012, which was the final year of his contract after the Yankees exercised their team option. “Last year was a super stressful season for me, man,” Swisher said. “I am not going to be stressed out like that this year. I’m going to have as much fun as I can and just enjoy it. This is such a great place to play. I’m just enjoying every minute of it.” Swisher continued with his hot start by smacking an opposite-field grand slam over the left-field wall, inching the Yankees closer at 9-5. Cano followed up with a double off the wall, ending Padilla’s afternoon. Off Matt Albers, Rodriguez hit a groundball to short that Aviles bobbled, giving the Yankees runners at the corners with none out and Teixeira stepping to the plate. Teixeira, who had homered from the right side of the plate off lefty Doubront in the previous inning, batted from the left side against the righty Albers. With a 2-and-2 count, Teixeira reached out and smacked an outside pitch over the wall for an opposite-field three-run homer, bringing the Yankees within one: 9-8. After scoring seven in the seventh inning, the Yankees weren’t done beating up the Red Sox bullpen. In the eighth lefty Franklin Morales, who retired the Yankees in the seventh in relief of Albers, surrendered a leadoff single to Nuñez, putting the tying run on first. Valentine called on closer Alfredo Aceves for a six-out save. After walking Jeter, Aceves surrendered a sky-high double to Swisher that bounced off the center-field wall, scoring Nunez and Jeter, giving the Yankees a 10-9 lead and Swisher six RBIs for the game. After walking Cano intentionally and then walking Rodriguez to load the bases with none out, Aceves surrendered a line-drive double to Teixeira that bounced over the short wall in the right-field corner. Swisher and Cano scored, Rodriguez went to third, and the Yankees now led 12-9. Like Swisher, Teixeira also had six RBIs. After intentionally walking Curtis Granderson to load the bases again, Aceves was replaced by Justin Thomas. Valentine was met with a chorus of boos when he marched onto the field to lift Aceves; he responded by tipping his cap to the fans. He later said, “I’ve been booed in a couple of countries; a few different stadiums. I don’t want to be booed.” It took only two pitches to get two outs as Raul Ibañez hit into an unassisted double play at first base. But Martin sent the first pitch he saw from Thomas to the center-field wall for a double, scoring Rodriguez and Teixeira and extending the Yankees’ lead to 14-9. Jeter’s single off Junichi Tazawa plated Martin, giving the Yankees a 15-9 lead that would stand as the final score. “You’re down 9-0 and Tex hits what looks like an innocent home run. Then we come back with back-to-back seven-run innings,” Yankees manager Joe Girardi said after the game “I don’t think I’ve ever been a part of that.” “I don’t like to lose. I don’t know anybody who does,” Aviles said. “This wasn’t fun at all. I don’t want to see it if it gets any worse.” While it might not have gotten any worse than this particular game, the Red Sox did do plenty of losing in 2012, 93 games to be exact, and finished in last place. Valentine was fired after the last game of the season. -

6 out of 10, 69 seconds. I had three where-did-I-go-to-college questions. I missed all three. Just once I'd like to be asked where Ken Stabler went to college (Alabama.)

-

Great and Historical Games of the Past

Yankee4Life replied to Yankee4Life's topic in Baseball History

June 23, 1984: The Sandberg Game The Chicago Cubs were struggling. For the first two months of the season, they were a cute story. Since mid-May, the lovable losers of recent years had spent much of their time in first place in the National League East. Starting on June 6, however, the team lost ten of 16 games. The lowlight was a four-game sweep in Philadelphia in which they were outscored, 33-13. That knocked them out of the top spot, and it looked for a while like things were reverting to form at 1060 West Addison. As the day began on June 23, the Cubs found themselves in third place, a game and a half behind the division-leading Mets. The St. Louis Cardinals were in town, a team that was barely treading water at 34-37. The Cubs sent Steve “Rainbow” Trout to the mound, while the Cardinals countered with virtual-unknown Ralph Citarella, making his first big-league start. It was a nationally televised Saturday afternoon Game of the Week on NBC, with Bob Costas and Tony Kubek doing the honors. Before the contest began, Kubek observed, “The wind…blowing in from right field, so it’ll kill any ball hit to the right field sector. Anything hit to left-center will be…given a little help, if it’s up in the air.” It looked at the outset like the Cubs’ swoon was going to continue. Trout bombed early, and by the time they came to bat in their half of the sixth, they were down 9-3. Suddenly, however, their bats woke up. They scored five runs in that frame, sending Citarella to the showers, to quickly turn a yawner into a tense, exciting one-run game. That is how the score remained until the bottom of the ninth. “This has been one entertaining ball game, folks,” Costas commented, just in case any of the viewers at home didn’t already know it. On the mound for St. Louis was their ace reliever (and former Cy Young Award-winner with the Cubs) Bruce Sutter, who had entered the game in the bottom of the seventh. He had faced four batters so far, and gotten four harmless groundball outs. Leading off for the North Siders was their fine young second baseman Ryne Sandberg, who already had three singles and four RBIs in the game. On a 1-1 count, Sandberg took Sutter downtown, drilling a hanging curve over the left-center-field bleachers, onto Waveland Avenue. The game was tied, to the delight of the frenetic Wrigley Field faithful. The Cubs got the winning run to third base with two out in the person of Gary Matthews, but a groundout ended the inning, sending the game into extras. St. Louis put a quick stop to the buzz going on at the ballpark, by scoring a pair of runs in the top of the tenth. Sutter was still on the mound, and Chicago appeared to have its work cut out as the bottom half of the inning loomed. Two quick ground-ball outs did nothing but deflate any remaining air left in the Cubs’ party balloon. But Bob Dernier walked, and Sutter was left to again face Sandberg. The count went to 1-1, at which point Costas began rapidly reciting to the TV crowd that “our game today was produced by Ken Edmundson, directed by Bucky Gunts, Mike Weisman is the executive producer of NBC Sports, coordinating producer of baseball Harry Coyle. One-one pitch.” Sutter served. Sandberg swung. Kubek belted out a distended “Ooooooh myyy!” Costas was surely more descriptive: “And he hits it to deep left center! Look out! Do you believe it! It’s gone!” Both said nothing for the next 50 seconds. Viewers across the nation watched dumbfounded as 38,079 people suddenly went certifiably insane at Wrigley Field. In the next booth over from Costas and Kubek were Harry Caray, Lou Boudreau, and Milo Hamilton, who had spent the afternoon taking turns describing the game for Chicago’s WGN radio. As Sandberg’s second home run soared toward the bleachers, the three went into a collective fit of frenzy, and Caray’s voice was nearly drowned out in his broadcast partners’ delirious “Oh-hohs!” and “Hey-heeeeys!” “THERE’S A LONG DRIVE,” Caray shouted. “WAY BACK! MIGHT BE OUTTA HERE! IT IS! IT IS! HE DID IT! HE DID IT AGAIN! THE GAME IS TIED! THE GAME IS TIED! HO-LY COW!” It was Caray at his flabbergasted finest. “EVERYONE IS GONE BANANAS! HO-LY COW! WHAT WOULD THE ODDS BE,” Caray asked, his voice betraying his emotion, throwing out the question to anyone with a calculator, “IF I TOLD YOU THAT TWICE SANDBERG WOULD HIT HOME RUNS OFF BRUCE SUTTER?!” Cardinal manager Whitey Herzog kept Sutter in the game. “Here now is Gary Matthews,” Caray noted. “C’MON, YOU GUYS!” But the guys didn’t come on. Matthews grounded out, and the inning was over, much to the relief of Sutter. St. Louis threatened but didn’t score in the 11th. Finally, mercifully, Dave Rucker replaced Sutter to start the Cub half of the inning. Leon Durham led off with a walk, stole second, and advanced to third as catcher Darrell Porter’s throw bounced into center field. Jeff Lahti replaced Rucker on the mound. Keith Moreland and Jody Davis were both intentionally walked to set up a force at any base. “What a ballgame!” Caray exclaimed, apparently still unable to believe what he had witnessed moments before. “Hey! Was that 23-21 game against the Phillies any more exciting?” he asked, referring to a legendary 1979 Wrigley Field game (actually 23-22). “No, nope, no way,” Boudreau and Hamilton stated emphatically. Dave Owen, the last position player available on the Cub bench, came on to pinch-hit. A switch-hitter, he batted left-handed against the righty Lahti. The trouble was, Owen was hitting .133 from the left side. It would not matter this day. Owen drove a single into right field, Durham scored, and just like that, the rollercoaster affair had come to an end. “CUBS WIN!” Caray shouted. “CUBS WIN! CUBS WIN! HO-LY COW! LISTEN TO THE CROWD!” After letting the noise wash over him for a few seconds, Caray declared: “I NEVER SAW A GAME LIKE THIS IN MY LIFE, AND I’VE BEEN AROUND A LONG LIFE! WHAT A VICTORY! WHAT A VICTORY! LISTEN TO THE HAND THE CUBS ARE GETTING!” Costas, on the other hand, chose a more understated description of Owen’s hit. “That’s it!” Moments later, before cutting to a commercial, he would confess, “Can’t remember the last time I saw a better one!” Indeed, neither could many people. It was a thrilling game, an instant classic, highlighted by two unforgettable at-bats involving two future Hall of Fame players in Sutter and Sandberg. It was a coming-out party, both for Sandberg and the Cubs, as their grand performances occurred on a national stage. Back in the days before the proliferation of cable television, NBC’s Game of the Week was so named because it was just that. For just about everyone, it was the only baseball game they could watch during the week, other than their local team’s broadcasts. The victory was a catalyst for the Cubs, who went on to win the division title that year. For Sandberg, it put his name in the public consciousness, and started him on the way to a glorious career in Cub pinstripes. “It is the kind of stuff of which Most Valuable Player seasons are made,” sportswriter Dave Van Dyck proclaimed soon after the game. Indeed, Sandberg was named the NL MVP in 1984. He recalled years later, “It was a one-game thing that elevated my thought of what I was as a player, more of an impact-type of a guy, a game-winning type of a player.” As the decades passed, the contest was elevated to the status of myth, eventually becoming known simply as “The Sandberg Game.” To many Cubs fans, the game became a cultural touchstone. “Fans come up to me all the time and they want to talk about that game,” Sandberg says. “They tell me where they were. They were either driving in a car listening to the game…or they were at the game or watching it on TV. They were calling their relatives, (saying) ‘you’ve got to turn this game on!’” Nearly lost in all the brouhaha was the fact that Willie McGee, star center fielder for the Cardinals, hit for the cycle that day, with six RBIs. For Sutter, it was the low point of perhaps his most brilliant season, as he finished with a career-high 45 saves and a 1.54 ERA. Reflecting back on his days on the diamond, Sandberg admitted, “It was nothing to [Sutter’s] career. It was everything to mine.” -

7 out of 10, 68 seconds. These were challenging today.

-

8 out of 10, 60 seconds. I got this on a Tuesday? Amazing.

-

10 out of 10, 67 seconds. The time wasn't there because these questions today really made me think. Some of them anyway.

-

Ever since you've started you have done a great job. Keep it up. 👍 Because of you I was haunted by the ghost of George Steinbrenner and he yelled at me for losing last month. When I reminded him that I lost to a fellow Yankee fan he said never mind and went away. 😄

-

10 out of 10, 34 seconds. Starting better than last month!

-

Great and Historical Games of the Past

Yankee4Life replied to Yankee4Life's topic in Baseball History

This is the greatest game I have ever seen. I can still recall how nervous I was in the ninth inning. October 2nd, 1978: And a shortstop shall lead them. Baseball purists long for the days when baseball games, either regular-season or the World Series, were played under afternoon skies. Before the lure of television money and advertising dollars, baseball was an afternoon game. One with its one pace, no time clock, and moving with the ease of the summer breeze. But owners saw the revenue potential of playing home games, “under the lights.” With the addition of an extra layer of playoffs and the need to televise every postseason game, one will see a handful of games being played in the afternoon. Many may still argue that it is not enough. For it’s one of the simple pleasures of playoff baseball, watching the action in the crisp, cool fall air. There probably is not another region in the United States that better displays nature’s beauty in autumn than the New England states. The foliage is breathtaking and the scenery is magnificent with the yellow, orange, red, and brown leaves as windbreakers make a return appearance from the hall closet. It was within this setting that the New York Yankees traveled to Fenway Park to face their arch-rival Boston Red Sox in a chips-to-the-middle-of- the-table, winner-take-all ballgame. Both teams ended the season with a 99-63 record. New York took the season series, winning nine of 16 games. Boston led the third-place Yankees by 11½ games at the All-Star break and looked to be searching for the “cruise control” switch to coast to a division title. With one month to go in the season, Boston still led the Yankees by 6½ games. The Yankees went head-to-head with Boston seven times in September. The Bronx Bombers took six of seven and pulled ahead of the Bosox by 2½ games on September 17. But Boston had a resurgence, posting a 12-2 record to close the season. Heading into the season’s final game, the Yankees held a one-game advantage. But Cleveland defeated New York, 9-2, while Boston topped Toronto, 5-0. The result was a one-game playoff at Fenway Park. There had only been one other tiebreaker playoff game in American League history. That game, too, was staged at Fenway Park, 30 years earlier on October 4, 1948. Cleveland beat the Red Sox, 8-3, to claim the AL flag. The pitching matchup featured that season’s Cy Young Award winner in the AL, Ron Guidry. “Louisiana Lightning,” as he was called because of his roots in the Bayou State, was 24-3 with a 1.72 ERA. He had started three games against Boston in 1978, going 2-0. Even though Guidry was tabbed with only three days’ rest, he declared that he was ready to go. Red Sox manager Don Zimmer sent Mike Torrez (16-12, 3.92 ERA) to the hill. Torrez signed as a free agent with Boston after pitching half of the year with New York in 1977. He proved to be a valuable asset for the Yankees. He posted two complete-game victories in the ’77 World Series as the Yankees won their first world championship since 1962. Boston broke on top in the bottom of the second inning when Carl Yastrzemski homered to right field off Guidry for a 1-0 lead. The Red Sox did not cash in on an opportunity to increase their lead in the third inning. George Scott doubled to center field. He moved to third base on a sacrifice bunt by Jack Brohamer. But Guidry settled down to retire Rick Burleson and Jerry Remy and escaped the inning unscathed. Other than Mickey Rivers, Torrez was having little trouble with his old teammates. Rivers walked in the first inning and stole second. But he was left stranded. In the top of the third inning, Rivers smacked a two-out double to right field, but again did not score. In the bottom of the sixth, Boston increased its lead to 2-0. Burleson led off with a double to right field. Remy laid down a bunt to third base and Burleson took third. He scored when Jim Rice singled to center field. The Yankees mounted their comeback in the top of the seventh inning. With one away, Chris Chambliss singled to center field. Roy White followed suit with another base hit to center. Yankee manager Bob Lemon sent the left-handed Jim Spencer to pinch-hit for Brian Doyle. Spencer flied out to left field. Bucky Dent came to the plate and sent a Torrez pitch high over the Green Monster to give the visitors a 3-2 lead. The partisan crowd of 32,925 at Fenway fell silent as Dent made the grand tour around the bags. For Dent, the number-nine hitter in the Yankees lineup, it was his fifth home run of the year. New York owner George Steinbrenner was watching the game from the box seats by the Yankees’ third-base dugout with the club president, Al Rosen. “Al called Bucky’s home run just before he hit it,” the Boss said. “ ‘He’s gonna hit one out,’ and sure enough he did. It couldn’t happen to a finer young man.” However, the Yankees were not done. Rivers walked for the second time in the game. Zimmer pulled Torrez from the game and Bob Stanley replaced him. Rivers stole his 25th base of the season, and scored when Thurman Munson doubled to center field. Reggie Jackson led off the eighth inning by once again showing that his “Mr. October” moniker was well deserved. He blasted his 27th home run of the year to right field off Stanley. The Yankees’ lead was now stretched to 5-2. Guidry gave way to Goose Gossage in the bottom of the seventh inning. Goose was still on the mound in the eighth when the Bosox mounted a comeback of their own. Remy led off the frame with a double to right. After Rice flied out, Remy scored when Yastrzemski singled to center field. Carlton Fisk followed with another single to center and Yaz moved up to second base. He scored one batter later when Fred Lynn singled to left field. Lynn’s RBI cut the Yankees’ lead to one, 5-4, headed to the ninth inning. The Yankees were unable to add another run as the action moved to the bottom of the inning. With one out, Burleson walked and Remy singled to right field. Burleson took second on the base hit. He moved to third when Rice flied out to right field. But it was there where Burleson would stay. He was unable to close the final 90 feet needed for a tally when Yastrzemski popped out to Yankees third baseman Graig Nettles in foul ground. It was Gossage’s 27th save of the year. The New York Yankees were the champs of the AL East Division. “Well, I’ll tell you, I was dreaming, dreaming about something like that,” Dent said. “There’s no way you can feel tired now. This is all we’ve been playing for, the playoffs.” “This is the worst feeling I’ve had as a professional,” Remy said. “We have nothing to be ashamed of. The Yankees have a great club and we fought back and took them to the final out in the bottom of the final inning.” “It just wasn’t meant to be, that’s all,” Yastrzemski said. “But I’ll tell you something. Yaz is gonna be on a world champion before he retires from this club. There’s just too much talent on this club not to win it.” The Yankees went on to defeat the Kansas City Royals in four games in the ALCS. Similarly, they defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series in six games. For the Bombers, it was their 22nd world championship. For Yastrzemski, his proclamation did not come true. He retired after the 1983 season. The Red Sox did not return to the postseason until three years later, in 1986. -

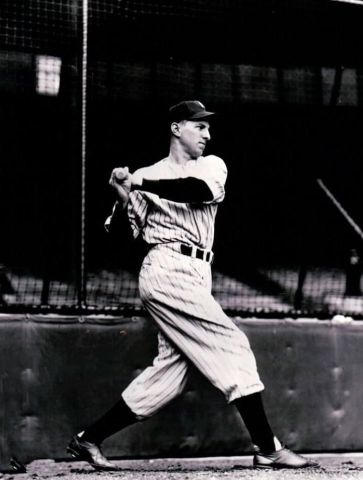

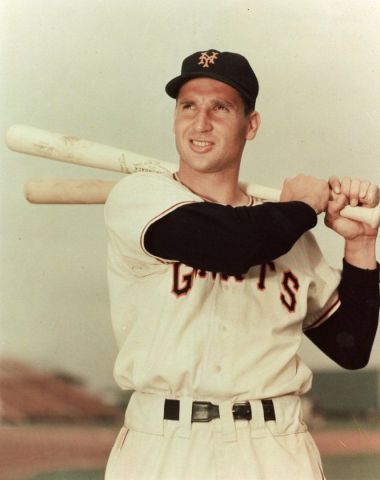

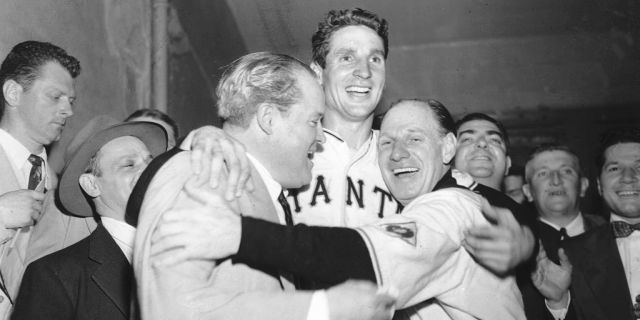

With the first day of the new year I decided to start up a new section here in the baseball history thread about famous games of the past. The first one to start off this will be the exciting 1951 playoff game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants on October 3rd, 1951. It’s the third and final National League playoff game and the winner gets to go on to face the American League Champion New York Yankees. October 3, 1951: The Giants Win The Pennant! On August 11, 1951, the second-place New York Giants trailed their rivals, the Brooklyn Dodgers, by 13 games. From that point until the end of the season, the Giants won 39 of their final 47 games, an incredible .830 clip. The 154-game season ended with both clubs tied for the top spot in the National League, necessitating a three-game playoff series. After splitting the first two contests, the foes faced off at the Polo Grounds on October 3 for the deciding game. Despite the high stakes, it was a relatively-disappointing crowd that made its way to the ballpark that afternoon. Perhaps it was the threat of rain in the forecast, or maybe the 10-0 drubbing that the Dodgers had inflicted on the Giants the previous day. Whatever the excuse, only 34,320 fans were in attendance. In the ensuing decades, tens of thousands more would claim that they were there. What the no-shows missed was one of the most legendary games in baseball history. The Giants were managed by Leo Durocher, who chose Sal “The Barber” Maglie as his starting pitcher. Maglie had gotten his nickname either because he usually looked like he hadn’t shaved, or because the fearless pitcher liked to welcome batters to the plate with a little chin music. He had won 23 games so far that season, including five against Brooklyn. His mound opponent for Charlie Dressen’s Dodgers was hard-throwing Don Newcombe, who had won 20. The Dodgers drew first blood, when Pee Wee Reese scored on a one-out single by Jackie Robinson in the opening frame. Maglie pitched his way out of further damage, however. In the bottom of the second, the Giants Whitey Lockman singled with one out, bringing up Bobby Thomson, New York’s 27-year-old third baseman, who had been sizzling down the stretch. Earlier, on his way to the ballpark, Thomson had said to himself that it would be great if he could somehow get three hits that day. He got off to a good start in this at-bat, lining one down the left field line. Thinking double all the way, he rounded first with his head down, racing for second. The Dodgers left fielder, Andy Pafko, had a rifle for an arm, and Lockman, not wanting to get thrown out at third, held at second. Pafko threw the ball to shortstop Reese. Thomson was suddenly caught in no-man’s land between first and second, and he was out on Reese’s relay to first baseman Gil Hodges. It was a costly base-running gaffe by Thomson. Instead of runners on first and second with one out, the Giants now had a runner on second with two down. The next batter, Willie Mays, flied out to end the inning. For the moment, Thomson wore the goat horns. In the darkening gloom, the Polo Grounds lights were turned on. In the fifth, Thomson, still wielding a hot bat, doubled to left. His mates, however, were unable to drive him in, and the score stood 1-0 in favor of the Dodgers. It remained that way until the seventh, when Thomson’s deep fly to center scored Monte Irvin from third. In the eighth, the wheels fell off for the Giants and the exhausted Maglie, as the Dodgers scored three runs to take a commanding 4-1 lead before the Barber was replaced by Larry Jansen. Newcombe, meanwhile, was seemingly growing stronger. Then came the bottom of the ninth. Many of the Polo Grounds crowd had already begun making their way to the exit ramps. Alvin Dark singled to open the inning. The next batter, Don Mueller, noticed that Dodger first baseman Gil Hodges was playing close to the bag, as Dark edged his way off first. It was an odd strategy on Hodges’s part; there wasn’t much chance of Dark attempting to steal. The Giants, after all, needed base runners. Mueller hit a slow grounder to Hodges’s right, just out of his reach. Had the first baseman been playing wider of the bag, he may have easily gobbled it up and started a double play. It went as a single to right field, however, with Dark taking third. Monte Irvin, the leading RBI man on the Giants and their best clutch hitter, fouled out to Hodges for the first out. At that point, an announcement was made in the press box that World Series credentials for Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field could be picked up later that evening at the Biltmore Hotel. Lockman, the next hitter, doubled to left, scoring Dark and sending Mueller to third. Mueller slid awkwardly into the bag, injuring his ankle. Thus, in the middle of the mounting excitement, the game was halted for several moments as Mueller was carted off the field, pinch-runner Clint Hartung taking his place. “The corniest possible sort of Hollywood schmaltz,” wrote Red Smith, “stretcher bearers plodding away with an injured Mueller between them, symbolic of the Giants themselves.” Next up, Bobby Thomson. To face him, Dressen brought in Ralph Branca. The Brooklyn righty had been the starter in Game One, giving up a homer to Thomson but pitching well in a 3-1 loss. Gordon McClendon was calling the game on radio for the Liberty Broadcasting System. “Boy, I’m telling you!” he declared. “What they’re going to say about this one I don’t know!” Branca somehow sneaked a fastball down the middle for strike one. “A ball I should have swung at,” Thomson, a fastball hitter, admitted later. At 3:58 pm, Branca’s second pitch, another fastball, came in high and tight. Thomson swung, his uppercut driving the ball deep toward the corner in left. Pafko, dashing toward the high wall, ran out of room. The ball landed in the first row, just above the 315 ft. sign for a three-run home run. Game over. The Polo Grounds shook as the euphoric crowd erupted. Joe King wrote in The Sporting News, “(Thomson’s homer) touched off scenes in this place which never before had been witnessed in connection with the winning of a pennant.” By any measure, and for pure excitement, Thomson’s home run, referred to down the years as “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” belongs on the short list of the most legendary in baseball history. Some consider it the most famous blast ever. Much of the mystique surrounding the home run lies in the iconic, delirious radio call by Giants broadcaster Russ Hodges (“The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!”) Dodger broadcaster Red Barber’s call summed it up: “It is…a home run! And the New York Giants win the National League pennant and the Polo Grounds goes wild!” Gordon McClendon described the home run this way: “Going, going gone! The Giants win the pennant!” Then, after a brief pause, “I don’t know what to say! I just don’t know what to say! It’s the greatest victory in all of baseball history!” Ernie Harwell, calling the game on the Giants television network, simply said “It’s gone!” Felo Ramirez, describing the game in Spanish for Latin-American listeners, cried “Los Gigantes son los campeones!” As Thomson raced around the bases to be greeted at home by a throng of ecstatic teammates, the stunned Dodgers began the long walk off the field. All except Jackie Robinson, who can be seen in a well-known photograph taken from center field looking in toward second base. The photo shows the scrum of players at home plate, with Thomson somewhere in the middle. Branca, head hanging, is walking dejectedly away from the mound. Robinson, standing all alone just beyond second base, his back to the camera, is staring, hands on hips, toward home, in order to make sure that Thomson actually touched the plate. It is one of the classic photos of sport, a poignant juxtaposition of dejection and giddy victory. Bobby Thomson had certainly gotten his three hits. Probably no one in the old ballpark was more delighted at Thomson’s home run than the on-deck hitter, rookie Willie Mays, who later admitted he was terrified at the prospect of having to bat in such a pressure-packed situation. Branca, of course, took the loss, while Jansen, who pitched one inning, got the win, his 23rd of the season. Attending the game that day was the motley quartet of comic actor Jackie Gleason, New York restaurateur Toots Shor, FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, and crooner Frank Sinatra (who had been given four tickets by Durocher). The group had been drinking all day, and just before Thomson hit his home run, Gleason unceremoniously threw up in the lap of Sinatra, a Giant fan. Said Sinatra later, “The fans are going wild and Thomson comes to bat. Then Gleason throws up all over me! Here’s one of the all-time games and I don’t even get to see Bobby hit that homer! Only Gleason, a Brooklyn fan, would get sick at a time like that!” Not only did the game feature perhaps the most famous home run ever hit, the most famous radio call in sports broadcasting history, and one of the most iconic sports photos, but it resulted in one of the most wonderful leads ever in a newspaper article. The day after the game, Red Smith, writing in the New York Herald-Tribune, opened his story “Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff” with the famous lines: “Now it is done. Now the story ends. And there is no way to tell it. The art of fiction is dead. Reality has strangled invention. Only the utterly impossible, the inexpressibly fantastic, can ever be plausible again.” Please continue for that famous Red Smith article. 1951 Dodger - Giant playoff By Red Smith Now it is done. Now the story ends. And there is no way to tell it. The art of fiction is dead. Reality has strangled invention. Only the utterly impossible, the inexpressibly fantastic, can ever be plausible again. Down on the green and white and earth-brown geometry of the playing field, a drunk tries to break through the ranks of ushers marshaled along the foul lines to keep profane feet off the diamond. The ushers thrust him back and he lunges at them, struggling in the clutch of two or three men. He breaks free, and four or five tackle him. He shakes them off, bursts through the line, runs head-on into a special park cop, who brings him down with a flying tackle. Here comes a whole platoon of ushers. They lift the man and haul him, twisting and kicking, back across the first-base line. Again he shakes loose and crashes the line. He is through. He is away, weaving out toward center field, where cheering thousands are jammed beneath the windows of the Giants’ clubhouse. At heart, our man is a Giant, too. He never gave up. From center field comes burst upon burst of cheering. Pennants are waving, uplifted fists are brandished, hats are flying. Again and again the dark clubhouse windows blaze with the light of photographers’ flash bulbs. Here comes that same drunk out of the mob, back across the green turf to the infield. Coattails flying, he runs the bases, slides into third. Nobody bothers him now. And the story remains to be told, the story of how the Giants won the 1951 pennant in the National League. The tale of their barreling run through August and September and into October. . . . Of the final day of the season, when they won the championship and started home with it from Boston, to hear on the train how the dead, defeated Dodgers had risen from the ashes in the Philadelphia twilight. . . . Of the three-game playoff in which they won, and lost, and were losing again with one out in the ninth inning yesterday when—Oh, why bother? Maybe this is the way to tell it: Bobby Thomson, a young Scot from Staten Island, delivered a timely hit yesterday in the ninth inning of an enjoyable game of baseball before 34,320 witnesses in the Polo Grounds. . . . Or perhaps this is better: “Well!” said Whitey Lockman, standing on second base in the second inning of yesterday’s playoff game between the Giants and Dodgers. “Ah, there,” said Bobby Thomson, pulling into the same station after hitting a ball to left field. “How’ve you been?” “Fancy,” Lockman said, “meeting you here!” “Ooops!” Thomson said. “Sorry.” And the Giants’ first chance for a big inning against Don Newcombe disappeared as they tagged Thomson out. Up in the press section, the voice of Willie Goodrich came over the amplifiers announcing a macabre statistic: “Thomson has now hit safely in fifteen consecutive games.” Just then the floodlights were turned on, enabling the Giants to see and count their runners on each base. It wasn’t funny, though, because it seemed for so long that the Giants weren’t going to get another chance like the one Thomson squandered by trying to take second base with a playmate already there. They couldn’t hit Newcombe, and the Dodgers couldn’t do anything wrong. Sal Maglie’s most splendrous pitching would avail nothing unless New York could match the run Brooklyn had scored in the first inning. The story was winding up, and it wasn’t the happy ending that such a tale demands. Poetic justice was a phrase without meaning. Now it was the seventh inning and Thomson was up, with runners on first and third base, none out. Pitching a shutout in Philadelphia last Saturday night, pitching again in Philadelphia on Sunday, holding the Giants scoreless this far, Newcombe had now gone twenty-one innings without allowing a run. He threw four strikes to Thomson. Two were fouled off out of play. Then he threw a fifth. Thomson’s fly scored Monte Irvin. The score was tied. It was a new ballgame. Wait a moment, though. Here’s Pee Wee Reese hitting safely in the eighth. Here’s Duke Snider singling Reese to third. Here’s Maglie wild-pitching a run home. Here’s Andy Pafko slashing a hit through Thomson for another score. Here’s Billy Cox batting still another home. Where does his hit go? Where else? Through Thomson at third. So it was the Dodgers’ ballgame, 4 to 1, and the Dodgers’ pennant. So all right. Better get started and beat the crowd home. That stuff in the ninth inning? That didn’t mean anything. A single by Al Dark. A single by Don Mueller. Irvin’s pop-up, Lockman’s one-run double. Now the corniest possible sort of Hollywood schmaltz—stretcher-bearers plodding away with an injured Mueller between them, symbolic of the Giants themselves. There went Newcombe and here came Ralph Branca. Who’s at bat? Thomson again? He beat Branca with a home run the other day. Would Charley Dressen order him walked, putting the winning run on base, to pitch to the dead-end kids at the bottom of the batting order? No, Branca’s first pitch was a called strike. The second pitch—well, when Thomson reached first base he turned and looked toward the left-field stands. Then he started jumping straight in the air, again and again. Then he trotted around the bases, taking his time. Ralph Branca turned and started for the clubhouse. The number on his uniform looked huge. Thirteen.

-

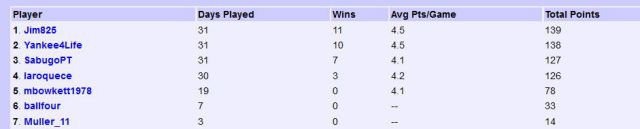

8 out of 10, 69 seconds. A so-so start because the time was bad. This month will be interesting because we have five Fridays in front of us and we end on a Friday so that means everyone will be piling up high scores on that day. Here is the final standings for December. Jim won by one point and he deserved to win. I did my best near the end but came up short.

-

Sure thing. These two days were tough.

-

Can I do a do-over? 😃

-

5 out of 10, 73 seconds. 1. How many teams participated in the 1954 World Cup, which was held in Switzerland? 2. Who managed Real Madrid before Carlos Queiros? 3. Which Houston Comet drafted in 2002, dunked in college? 4. Which of the following Clubs was not included in the NSWRL as an 'Expansion Club', between 1982 and 1988? 5. Where was Euro 1996 staged? These are the five I missed. I had no chance. Damned stupid questions. Good going Jim! You deserve it.

-

Just once. Fiebre and I ended in a tie.

-

Oh my God! Today was a tough one. Best of luck tomorrow Jim.

-