-

Posts

21576 -

Joined

-

Days Won

82

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Downloads

Everything posted by Yankee4Life

-

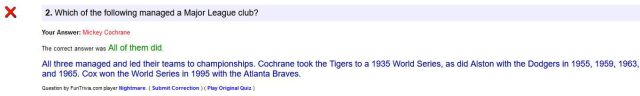

9 out of 10, 35 seconds. It should have been ten and I will show you why I said that. I knew the answer and I have no idea why I clicked on the wrong one excerpt maybe I was trying to go too fast. Well, this time it came back to bite me.

-

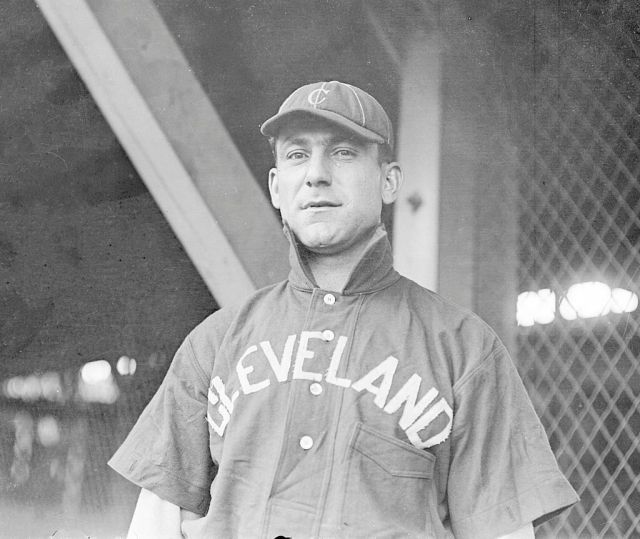

Roger Peckinpaugh Roger Peckinpaugh was one of the finest defensive shortstops and on-field leaders of the Deadball Era. Like Honus Wagner, the 5’10”, 165-lb. “Peck” was rangy and bowlegged, with a big barrel chest, broad shoulders, large hands, and the best throwing arm of his generation. From 1916 to 1924, Peckinpaugh led American League shortstops in assists and double plays five times each. As Shirley Povich later reflected, “the spectacle of Peckinpaugh, slinging himself after ground balls, throwing from out of position and nailing his man by half a step was an American League commonplace.” The even-tempered Peckinpaugh was equally admired for his leadership, becoming the youngest manager in baseball history when he briefly took the reins of the New York Yankees in 1914. Described as the “calmest man in baseball,” Peckinpaugh’s steadying influence later helped the Washington Senators to their only world championship, and won him the 1925 Most Valuable Player Award, making him the first shortstop in baseball history to receive the honor. From an early age, Roger took an interest in baseball, and probably received special instruction from his father, who had been a semipro ball player. When Roger was a boy his family moved to the east side of Cleveland, taking up residence in the same neighborhood as Napoleon Lajoie, the manager and biggest star of the Cleveland Naps. Roger grew up idolizing Lajoie, and matured into a fine all-around athlete, starring in football, basketball, and baseball at East High School. Lajoie noticed Peckinpaugh’s talent, and upon the youngster’s graduation from high school in 1909, offered him a $125 per month contract to play pro ball. Roger’s father was against his turning pro, so he asked his high school principal, Benjamin Rannels, for advice. Probably aware of Roger’s love for baseball, Rannels urged Peck to sign the contract, advising him to allow himself three years to make it to the majors. If he didn’t make it, then he should go to college. Peck was a regular in two years. In 1910 the Naps sent Peckinpaugh to the New Haven Prairie Hens of the Connecticut State League for some seasoning before calling him up to the big league club in September. Peckinpaugh hit only .200 over 15 games in his first major league trial, and was farmed out the Pacific Coast League’s Portland Beavers for the entire 1911 season. Peck made the big club to stay in 1912, but the right hander only hit .212 in 70 games. Based on that poor showing, the Naps gave the starting shortstop job to another youngster, Ray Chapman, and in May 1913 traded Peck to the New York Yankees for Bill Stumpf and Jack Lelivelt. Yankees manager Frank Chance installed Peck at shortstop, where he would stay for the next eight and a half years. Given a chance to play regularly, Peck hit a respectable .268 in 1913, as the Yankees finished seventh. In 1914, Peckinpaugh’s average dipped to .223, though he played all 157 games, swiped a career-high 38 bases, and displayed the strong arm and superior range that would soon win him plaudits as one of the league’s finest defensive shortstops. Though he was only 23 years old, Peckinpaugh also emerged as one of the steadying influences in a distracted clubhouse. “The Yankees were a joy club,” Roger later remembered. “Lots of joy and lots of losing. Nobody thought we could win and most of the time we didn’t. But it didn’t seem to bother the boys too much. They would start singing songs in the infield right in the middle of the game.” In recognition of his leadership abilities, Chance named Peckinpaugh captain of the team, and the young shortstop soon won the confidence of all the players. When Chance resigned with three weeks left in the season, the Yankees made Peck the manager for the rest of the season. He still holds the record as the youngest manager in major league history. Jacob Ruppert and Cap Huston bought the New York franchise after the 1914 season and started turning the Yankees into winners. Ruppert hired Wild Bill Donovan to take the managerial reins but he kept Peck as captain. With the Federal League dangling big money in front of established stars, the Yankees signed Peck to a three-year contract at $6,000 per year for 1915 to 1917. While he continued to post pedestrian batting averages over that span–topping out at .260 with 63 runs scored in the final year of his contract–Peckinpaugh repaid the Yankees’ loyalty with his glove, leading the league in assists in 1916 and double plays the following year. To aid his fielding, Peck liked to chew Star plug tobacco, and then rub the juice into his glove. “[It] was licorice-flavored and it made my glove sticky,” he later said. He also used the tobacco to darken the ball, “and the pitchers liked that. The batters did not, but, what the hell, there was only one umpire.” According to Tris Speaker, opponents were able to cut down on Peckinpaugh’s batting average by cheating to the left side, where the right-handed dead pull hitter found the vast majority of his base hits. “Peck usually hits a solid rap when he does connect with the ball,” Speaker explained to Baseball Magazine in 1918. “But he has the known tendency to hit toward left field. Consequently at least four men are laying for that tendency of his….A straightaway hitter whose tendency was unknown might hit safely to left field where the very same rap by Peckinpaugh would be easily caught.” But after hitting just .231 in 1918, Peck began hitting the ball with more power, posting a career-high .305 average in 1919 with seven home runs. He followed up that performance with back-to-back eight-homer seasons in the lively ball seasons of 1920 and 1921, drawing a career-high 84 walks in the latter season. As further evidence of his expanding offensive versatility, Peckinpaugh also laid down 33 sacrifices, fifth best in the league. Two years later, he would lead the league with 40 sacrifices, and would eventually finish his career with 314 sacrifices, eighth most in baseball history. In his first World Series in 1921, Peckinpaugh played poorly in the Yankees’ eight game loss to the New York Giants, as he batted just .194 and his crucial error in the final game allowed the Giants to win 1-0 on an unearned run. In the off-season Babe Ruth complained about the managerial skills of Miller Huggins (not for the first or last time) and said the Yanks would be better off if Peck managed them. Probably to avoid more conflict, New York traded Peck and several teammates to the Red Sox for a package that included shortstop Everett Scott and pitcher Joe Bush. However, three weeks later, Senators owner Clark Griffith, sensing that his team was one shortstop away from contention, managed to engineer a three corner trade in which the Red Sox received Joe Dugan and Frank O’Rourke, Connie Mack‘s Athletics received three players and $50,000 cash, and the Senators received Peckinpaugh. The veteran shortstop teamed with the young second baseman Bucky Harris to form one of the best double play combinations in the American League. Everything fell into place by the 1924 season when owner Griffith appointed Harris the manager. Harris considered Peck his assistant manager, and together they led the Senators to back-to-back pennants in 1924 and 1925. Peck was the hero of the 1924 World Series, .417 and slugging .583, including a game-winning, walk-off double in Game Two. However, while running to second base (unnecessarily) on that hit, Peckinpaugh strained a muscle in his left thigh, which sidelined him for most of Game Three and all of Games Four and Five. But in what Shirley Povich called “the gamest exhibition I ever saw on a baseball field,” Peckinpaugh took the field for Game Six with his leg heavily bandaged and went 2-for-2 with a walk before re-aggravating the injury making a brilliant, game-saving defensive play in the ninth inning. Although Peckinpaugh had to sit out Game Seven, he had already done more than his share to bring the Senators their first world championship. Peckinpaugh came back strong in 1925 and had a fine season. He batted .294 (approximately the league average) as the Senators won their second straight pennant. In a testament to his fielding and leadership abilities, the sportswriters voted Peck the American League MVP in a narrow vote over future Hall of Famers Al Simmons, Joe Sewell, Harry Heilmann, and others. Despite his strong performance, Peck’s legs continued to give him trouble, and by the start of the World Series they needed to be heavily bandaged. After carrying the Senators in the 1924 World Series, Peckinpaugh sabotaged them in 1925, turning in one of the worst performances in Series history. He committed eight errors, a Series record that still stands, although Peckinpaugh later groused that “some of them were stinko calls by the scorer.” Three of Peck’s errors led directly to two Senators losses, including an eighth-inning miscue in Game Seven that allowed the Pirates to come from behind to capture the championship. Peckinpaugh’s two errors that day, however, were perhaps understandable, as the playing conditions were so wet that gasoline had to be burned on the infield to dry it off. Still, it was the second time (after 1921) that a World Series had been lost due to a Peckinpaugh error in the deciding game. Peck’s legs were giving out, and he would only play two more years in the big leagues. After retiring from the game following the 1927 season, Peckinpaugh accepted the managerial post for the Cleveland Indians. In five and a half seasons with Cleveland, Roger guided the club to one seventh place finish, one third place finish and three consecutive fourth place finishes before being fired midway into the 1933 season. After stints managing Kansas City and New Orleans in the minor leagues, Peck returned to skipper the Indians again in 1941, finishing in fifth place before moving into the Cleveland front office, where he remained until he retired from organized baseball after the 1946 season. Peckinpaugh retired with a .259 lifetime average, had 48 home runs and 740 runs batted in. His managerial record was 500 - 491.

-

Five people so far have perfect scores. Wow, what a way to start a month. We tied my friend. That's how I see it.

-

For the first time in our trivia games we have a tie at the top at the end of the month. Fiebre and I both had 175 points and will share the top spot. At the beginning of the day two days ago I had a four point lead but then two straight days of getting 4 out of 10 did me no good and Fiebre took advantage of it. He's great at this game and I give him a lot of credit. Now today I had 10 out of 10 in 44 seconds. A little too late.

-

That's great! I have never come close to a perfect score in this category. 👍

-

4 out of 10, 130 seconds. And that my friends is that. Throw in a where-did-he-go-to-school, soccer questions and what number did so-and-so wear (I had two of those!) and you can see why I only got four right. Now to see what Fiebre does. That guy is unbelievable. He just keeps coming at you.

-

4 out of 10, 88 seconds. These questions today were more than difficult. I think they were as tough as I've seen. How I got four I will never know.

-

4 out of 10, 97 seconds. The great equalizer for me in this trivia game. General\Intermediate means General\You suck for me. 😄 Nascar doesn't exist for me because I can't stand it. I never pay attention to it.

-

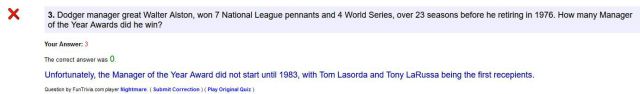

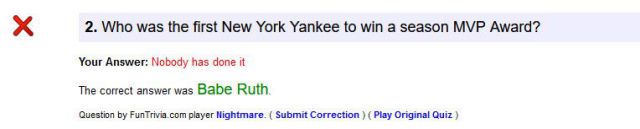

Who knows Jim? So I looked it up here on Baseball reference. The Most Valuable Player Award is given annually to one player in each league. The award began in 1911 as the Chalmers Award, honoring the "most important and useful player to the club and to the league". This award was discontinued in 1914. From 1922 to 1928 in the American League and from 1924 to 1929 in the National League, an MVP award was given to "the baseball player who is of the greatest all-around service to his club". Prior winners were not eligible to win the MVP award again during this time. The current incarnation of the MVP award was established in 1931. The Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA) votes on the MVP award at the conclusion of each season before the postseason starts.

-

8 out of 10, 49 seconds. I did terrible and let me show you why. As a Yankee fan I hang my head in shame. My excuse is that I read it too fast and therefore messed up. I'm ashamed. For my penance I will say something nice about Rafael Devers. He had a good season in 2023. There, that's it. Done. December is arriving on Friday Jim believe it or not. This has been a fast month and with the extra day in December it is going to make the trivia race even more exciting.

-

Thank you. I enjoy doing it. Every player I feature I learn something about. Baseball history is wonderful to read about. I've had many months like that too Jim, kind of like I am stuck in place and no matter what I did I couldn't get going. Usually it is watching Fiebre pass me by. Those "general" questions are coming so I am not home free yet.

-

Thank you very much Marty.

-

Napoleon Lajoie was the first star of the newly formed American League back in 1901. He was so popular that when he went to Cleveland the team was renamed the Naps. Let’s see that happen today. I doubt if any team will rename themselves the Ohtanis if he happens to sign with them. 😅 Anyway, I doubt you will miss this question again after this.👍 Nap Lajoie. Career .339 average with 3, 252 hits. A really good player.

-

I hope you don't mind but I have to correct you. You have helped here on this site in more than "one tiny way" as you put it. You have maintained the transaction thread for such a long time that we almost overlook how effortless you seem to do it. You don't miss a transaction and you are always on top of things. If a player is released we can be sure to read about it immediately or if the latest the very next day. You do a fantastic job at this and I just want you to know this. Thank you for saying that. I think what he does around here is so important. You are referring to KGBaseball. He did make good rosters but I can not point to them in the download section because he, along with a group of other modders pulled their modws from this website and brought them over to EAmods, which is no longer around. His work was more than good enough to be featured here but that’s how it is. Others like UncleMo (audio) Spungo (Uniforms, etc) and a guy named piratesmvp04, who made two total conversion mods for Mvp 2004 do not have their work here either. Anyway, that’s that. However if you really want to see KG’s work just download the Mvp 2007 or 2008 mod because his rosters are there. That is the only remaining example of his work here and as far as I am concerned that is more than enough.

-

10 out of 10, 34 seconds. Now if the end of the month was tomorrow I'd be fine. I have done the same thing many times.

-

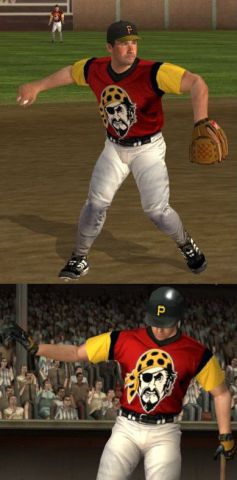

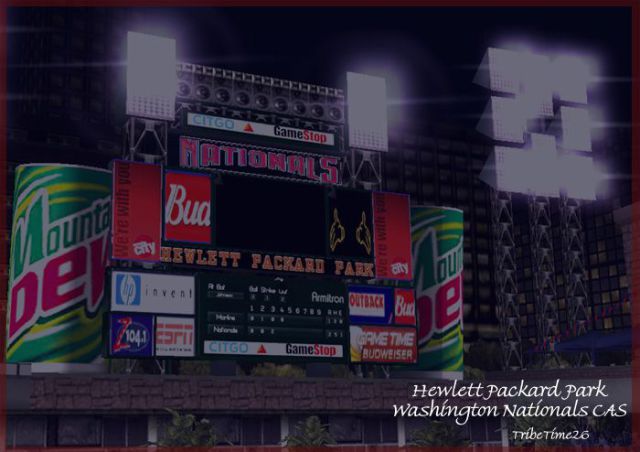

This week’s submission to the best of the best of the modders whose contributions to this website help make this website the number one baseball gaming site anywhere. One of the modders this week made uniforms for Mvp baseball 2004 and is a name only a few here now will recall. The other is a modder is someone who provided some minor fixes to the look of the game and once implemented made it look better. And our Behind the Scenes modder is someone who, while having some mods available for individual downloads, provided many portraits and cyberfaces for the Mvp 2006, ‘07 and ‘08 mods. IronForge It is unfortunate that IronForge did not continue to make uniforms when Mvp 2005 came out because he had a knack of making some very good ones just like the many other uniform makers that we have here. Maybe that was why he discontinued his mods but we’ll never know. His Bad News Bears uniform was a nice addition to my game and I recall placing it in one of the All-Star team uniform slots. His other uniforms such as his 1979 Oriole throwbacks were just as impressive. Keep in mind that you can use any of these mods in your Mvp 2005 game. Bad News Bears Uniforms (for Mvp 2004) Pirates Turn Ahead the Clock uniforms (for Mvp 2004) 1973 Pirates Throwback Away Uniforms (for Mvp 2004) 1979 Orioles Throwbacks (for Mvp 2004) Halofan Halofan was a dedicated and loyal Anaheim Angels fan. Notice that I said Anaheim. This caused a bit of controversy back when he was making his stadiums because some folks were commenting that he was pushing back too hard when Angels owner Arte Moreno renamed them to the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. He was having none of that and he made a stadium that showed how he felt. He had ads in the stadium that said savetheanaheimangels.com and the ad for the Los Angeles Times has been replaced with one for the Orange County Register. Also there are placements in the stands to show how he felt. All this plus a well-made stadium is a ball park worth checking out. I have always wondered how he felt when they officially changed the name to the Los Angeles Angels before the start of the 2016 season. Halofan’s Mvp 2005 Scoreboard fixes HaloFan’s “New” Icon Remover HaloFan’s Angel Stadium Of Anaheim - The Protest Edition: Day And Night Version Behind the Scenes Kriegz (better known as Tribetime26) Tribetime26 was a huge Cleveland Indians fan whose mods were mostly about the Indians be it his faces or portraits although he did branch out and do other teams too. His contributions were included in the very popular season mods from 2006 to 2008. He also made a fantasy Washington Nationals park not long after they left Montreal. TribeTime26s Chicago White Sox Portrait Pack v1.1 TribeTime26s Cleveland Indians Cyberface Set v1 TribeTime26s Tampa Bay Devil Rays Complete Photoset TribeTime26s Hewlett Packard Park (Washington Nationals CAS) v1.0 *I recommend you do not use any of the cyberfaces or portraits because they are just being posted here to show examples of his work. Putting these in your game will cause crashes. The ball park won’t.

-

9 out of 10, 49 seconds. I'm trying my best to come on strong but there's a lot of time for me to mess up.

-

10 out of 10, 39 seconds. I needed this a lot because I am running out of time this month.

-

8 out of 10, 72 seconds. A minor miracle today. I never do well in the General\Easier category.

-

9 out of 10, 55 seconds. A good comeback because I really needed it to keep up with you guys. You will not believe the one I missed. Laroquece was just talking about the Rockies in the shoutbox and here was the question.

-

Jack Bentley Many players in this thread you have heard of but it is my intention to have you walk away with some new information about every one of these players featured here. Today’s is about one of the first two-way players who played during Babe Ruth’s time and if his luck would have been a little bit better he would not be so obscure today. I always learn something about all of these players no matter how famous they were. The history of baseball is a fascinating and wonderful thing to discover. When the Los Angeles Angels signed Japanese superstar Shohei Ohtani, the baseball world has two-way players on the mind, yet the idea of the two-way player is far from a new one. Decades ago, it was not uncommon to find many a pitcher who handled the bat nearly as well as they performed on the mound. Few, however, truly excelled at both at the same time. One example from early in the 20th century was Jack Bentley. John Needles Bentley was born on March 8th, 1885, in a Quaker farming community in Sandy Spring, Maryland, to an affluent family. Living so close to the Washington Senators, Bentley was an ardent fan of the team. Indeed, the Senators would play an important role in his development as a professional. Soon after departing home for the George School in Newtown, Pennsylvania, a Quaker day school, Bentley became an accomplished pitcher. He would leave the George School at age eighteen, already a major-league prospect. It is reported that Bentley threw “several” no-hitters while in high school. Less than a year after becoming a student at the day school, Bentley was approached by Bert Conn, then manager of the Johnstown Johnnies in the Class B Tri-State League, a league which included teams in Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey. Conn offered him a contract to play the outfield at $75 a month, equivalent to slightly less than $1900 in current value, but the teenager turned him down. It was a pivotal time for Bentley. His father was enduring health problems that would eventually overcome him, and the farm had to be tended as well. This is where Julian Gartrell entered the picture. Gartrell, a doctor in the DC area, took notice of Bentley and mentioned him to his friend, Senators manager Clark Griffith. Bentley was playing for a county team by the time Dr. Gartrell found him, and after a particularly well-pitched game, the doctor suggested to Bentley that he go to Griffith Stadium to try out for the Senators. Bentley took that chance, and Griffith liked what he saw, though Bentley had no expectation that anything good would come of the tryout. Bentley was put on the mound by Griffith to pitch batting practice. Senators catcher John Henry, at the time, expected little to come of the eighteen year-old's performance. And yet, batter after batter looked baffled against the young lefty. After twenty minutes or so, Griffith had seen enough. He would offer Bentley a season-long contract for $600 ($100 per month). Bentley wouldn't accept it without first discussing it with his parents, who felt baseball wasn't a worthwhile vocation. The general atmosphere among professional ballplayers, where drinking, gambling, philandering, and generalized chicanery were commonplace, caused further hesitation in the minds of the Quaker family. After he gave his word that he would abstain from such activities, his parents gave their blessing. Bentley, amazingly, went straight to the majors, making his MLB debut on September 6th, 1913, against the New York Yankees. He entered the game in the ninth in relief of Joe Engel, with the score 9-1, Senators. He retired right fielder Frank Gilhooley on a fly ball to center fielder Clyde Milan, shortstop Rollie Zeider lined out to center as well, and catcher Ed Sweeney grounded out to second baseman Frank LaPorte. It was a low-pressure appearance for Bentley, but Griffith wanted to see what he could do without throwing him to the wolves just yet. Bentley made his first start for the Senators on October 1st against Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics. Again, he pitched brilliantly, allowing four hits in eight innings to get the shutout and his first win in the majors. Appearing in relief three days later vs. the Red Sox, Bentley tossed two shutout innings while allowing only one hit. By the time that Spring 1914 rolled around, Senators veteran Nick Altrock had taken a personal interest in Bentley's future. Bentley would spend the first two months with the big-league club, but despite posting a 5-7 record with a 2.37 ERA over 125 1/3 innings, Griffith still felt Bentley needed to spend a bit of time in the minors, sending him to the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association on June 12th. This was after he was given a new, $1800 contract for the 1915 season. Much of Bentley's newly-developed difficulty on the mound had to do with the Senators attempting to change his delivery, making him pitch from the stretch exclusively. This caused him an unspecified arm injury, for which he sought treatment after his demotion to Minneapolis. Unfortunately, the man he saw to treat his arm was none other than “Bonesetter” Reese, who had gained a sort of notoriety for his (ahem) nuanced approach to the various ailments of the baseball player. It was, perhaps, this series of events, as much as anything else, that set him on the path on which he found himself for much of the next four years. While Bentley would continue on the mound for Minneapolis in 1916, Baltimore Orioles owner Jack Dunn would acquire his services a little more than halfway into the season as part of a rebuilt roster that would become the best Orioles team since the 19th century. Dunn was aware of the sort of offense that Bentley could provide; in 1915 with the Millers, Bentley was primarily a pitcher and still struggling with the aforementioned shoulder injury (7-4, 3.18), though he was a key member of the pitching staff. In 1916, Bentley's numbers on the mound were less than stellar (8-6, 4.15), but in 78 at-bats he batted .308 with six doubles and two triples. As 1917 began, the Orioles got off to a hot start in the International League, with Bentley splitting time between the outfield and first base, batting .343 over 93 games. He added 17 doubles, 11 triples and five homers, but this would be far from his best season. He would take a hiatus in 1918 to join the war effort in Europe, being assigned to Camp Meade and making sergeant seemingly overnight. Initially, Bentley was expected to remain at Camp Meade, where he would be a drill sergeant, but fate would have other plans. By June in that same year, Bentley had earned his commission. Now a second lieutenant, he would be deployed with the 313th Infantry, eventually commanding Company L, and would see action in the Argonne. He would be transferred to the 125th on Armistice Day. It was an experience that would remain with him for the rest of his life. Bentley would be cited twice for bravery during his time in the European Theatre, earning the Distinguished Service Medal. By the time his tour was ending, he was being considered for a promotion to captain. Bentley would say that after he returned from the battlefield, he no longer held such fascination for opposing players as he did before. He had talked about how it sometimes filled him with awe that he was playing with and against the very same players he used to idolize. Now, they all just seemed like Regular Joes, to him. After the experience of seeing hundreds of men in life-or-death situations, his perspective changed dramatically. Whether or not that played a role in his transformation from successful pitcher to top-tier hitter is debatable. The numbers speak for themselves: in 1919, Bentley would bat .324 with 24 doubles, 10 triples and 11 homers in only 92 games. The following season was even better, as he would bat .371 with 39 doubles, 12 triples and 20 homers. Bentley posted 231 hits in 145 games, that year. But as good as he was then, the next season was nearly legendary. Leading the International League with an astounding .412 average, he also led in homers, hits and doubles, as well as slugging percentage (.665) and total bases (397). What made these numbers all the more impressive was the face that he also made 18 appearances on the mound, going 12-1 with a 2.34 ERA. After the 1922 season, when Bentley batted .351 in 153 games and dropped his ERA to 1.73 while going 13-2 in 16 appearances on the mound, Dunn decided to strike when the iron was red-hot. By that time, Bentley was ready to retire if he couldn't get back to the majors; the International League could keep players virtually as long as they wished, as they were not part of organized farm systems at that time. New York Giants manager John McGraw was desperate for left-handed pitching at the time, and even though a 22-year-old Lefty Grove was a teammate of Bentley's, the $100,000 price tag for Grove was just a bit too steep for the Giants. Dunn would sell Bentley's contract to the Giants for $72,500. Had the Giants kept Bentley either in the outfield or at first base, it's possible that he could have been far more useful to the team. However, George Kelly had him blocked at first, and the corner outfield spots belonged to Ross Youngs and Irish Meusel, with Casey Stengel as the primary 4th outfielder, Bentley was signed specifically to pitch full-time. By this point, he had missed a great deal of developmental time on the hill switching from pitcher to outfield/first base, as well as time lost to the war, and he had never played a full season in the majors in any capacity. Going 13-8 with a 4.48 ERA in 31 appearances, at least his bat carried over to the big leagues with him, as he batted .427 in 94 plate appearances with nine extra-base hits. His pitching stats improved in 1924 as he finished 16-5 with a 3.78 ERA in 28 appearances. His hitting tailed off (.265 average, 0 home runs and six RBI), but it would pick back up in 1925 (.303 average, three home runs, eighteen RBI) as his pitching totals spiraled downward (11-9, 5.04 ERA). Aside from modest totals in 1926 (.258 average with the Giants and Phillies), Bentley would spend the remainder of his pro career with various minor-league teams, where he would alternate between the field and the mound, still batting very well. However, his time on the mound was a poor contribution by comparison. For his career Jack Bentley recorded a 138-90 record on the mound, with a 4.61 ERA. He had a lifetime average of .291 with 7 home runs and 71 runs batted in. His was not a common sort of career, but it was certainly not the only one in which a professional player found success on the mound and at the plate. It would have been very interesting to see how well he would have done had he been properly managed.

-

Ok, who in the hell is Yerry De Los Santos and why do we need him?

-

6 out of 10, 58 seconds. God was with me here because I only knew two of the ten questions. I guessed right on the other four. Running out of time here to catch up.

-

6 out of 10, 91 seconds. These were really tough today and I was very fortunate to get six right.